Despite close proximity to Mount Vesuvius, many of the citizens of Herculaneum seem to have escaped the volcano’s devastation. Being so close may well have saved them. A smaller, seaside resort town, the city lay directly under the shadow of the volcano. Early rumbles and growls convinced most to flee. For years, historians and archeologists believed all the citizens had successfully evacuated, but later excavations made a gruesome discovery. They found the skeletons of over three hundred people near the shoreline, many bones charred like the city above. As ash and rock covered the surrounding countryside, Herculaneum burned.

Pleas for Assistance

The early morning expulsion of ash from Vesuvius did not reach Pompeii. The winds carried it mainly down the eastern slopes onto scattered farms and villas. Being directly at the base of the volcano, the citizens of Herculaneum felt intense tremors from the early warning. Utterly terrified, Lady Rectina of Herculaneum immediately sent messengers to plead for assistance from her friend, Pliny the Elder. A portly scholar of naturalism, he was also the admiral of the Roman fleet in the Bay of Naples. Pliny was staying at his seaside villa, also in Misenum, with his sister and her son, Pliny the Younger.

The messengers desperately raced up the coast, but it was a trip of several hours. They did not arrive until just after Vesuvius erupted in force. Pliny wondered at the unusual cloud, shaped like an umbrella pine, and alternating between shades of white and gray. Not yet fully aware of the dangers, and willing to incur some risk, he decided to sail closer to inspect it. He invited his nephew to join him, but Pliny the Younger, though tempted, decided to remain with his studies. Just before Pliny the Elder set sail, Rectina’s messengers arrived and delivered her letter, explaining that escape from sea was her only option and imploring him to help. He changed his plans, and rather than sailing closer out of scientific curiosity, he mobilized the navy and bravely set sail for the mountain, intending to rescue not only Rectina, but as many as he could.

Evacuation at the Shore

Meanwhile, in Herculaneum, effects of the eruption were fewer in the early hours. The wind had shifted south, and spared the city from the heavy ash and rock fall that pummeled Pompeii. Yet the falling ash may have limited or discouraged attempts to flee by land, and evacuation proceeded by boat. The citizens had to climb down a steep ladder to reach the water’s edge, and no evidence indicates panicked flight. None were trampled in a mass hysteria, mothers were even able to carry their children down the steep descent. Down below, boats on the shores began to ferry people out. Some private vessels even arrived from elsewhere in the bay, their owners selflessly risking their own safety save who they could. A number of citizens evacuated successfully, and the Roman navy was still sailing for the shore.

Unfortunately, they were never able to assist. “Ashes were already falling, hotter and thicker as the ships drew near, followed by bits of pumice and blackened stones, charred and cracked by the flames; then suddenly they were in shallow water, and the shore was blocked by the debris from the mountain” (Letters of Pliny the Younger). The admiral reluctantly gave the order to abandon their attempt, and to make for Stabiae, to the house of his friend, Pomponianus. No more ships could get in to help the trapped victims. Rectina’s fate remains unknown.

The Death of Herculaneum

In the early evening, the final remaining citizens filed down to the seaside, but there was no escape left. Over three hundred people remained on the shore in Herculaneum, men, women and children. They huddled together in the archways of the boathouses, sheltering from the falling ash, still hoping for rescue by sea. A rich woman wore all her rings to the water’s edge. A doctor had left his home with only his bag of medical instruments, a valiant effort to help the injured to the very end. Another was a soldier, perhaps keeping order, comforting the fearful, or maybe just sheltering with all the rest in hopes of survival.

About twelve hours after the eruption, the cloud of ash and gas above Vesuvius collapsed. A deadly pyroclastic surge raced down the mountainside. The first never reached Pompeii, but it barreled through the empty streets of Herculaneum to the shore. Some had ventured out of the boathouses to stand near the water’s edge, staring out in search of rescue. The surge hit them full blast and knocked them off their feet. The force was lessened some in the boathouses, but the thermal shock was so great that it killed every man, woman and child. Their deaths were mercifully quick. They didn’t even have time to cover their faces. The first and second surges set most of the town on fire. By the time the third surge hit, the first to reach Pompeii, Herculaneum was a lifeless city. Subsequent surges left it buried beneath twenty-three meters of volcanic material.

Pliny the Elder and his fleet made it safely to Stabiae, but their perils were far from over.

Sources: Pliny the Younger, The Letters of the Younger Pliny; Cassius Dio, Roman History; Cooley, Alison E.; Cooley, M. G. L., Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook; Capasso, Luigi, The Lancet, Department of medical history: “Herculaneum victims of the volcanic eruptions of Vesuvius in 79 AD.”

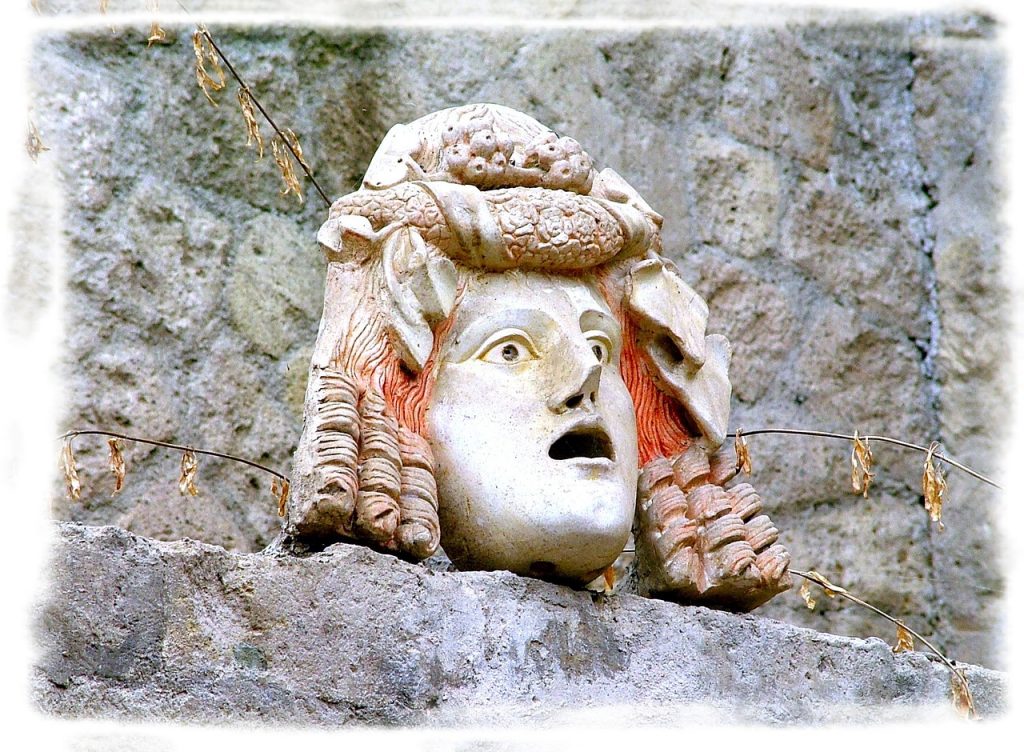

Photo: Herculaneum, Italy by Graham-H is licensed under CC0

This article was written for Time Travel Rome by Marian Vermeulen.

What to see Here:

Often unfairly overlooked in favour of the more well-known Pompeii, Herculaneum is nevertheless recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and the remains of ancient life that can be found here are almost unmatched anywhere else in the world. The pyroclastic flows which surged down from Vesuvius in 79 A.D. and buried the town and its inhabitants have helped preserve a snapshot of life in the Roman Empire.

There are a significant number of sites to be seen in Herculaneum. Of the larger public buildings to be seen, there is the forum, the basilica, and the baths. Some of the most notable remains at Herculaneum however, just as at Pompeii, are the domestic structures. The examples at this site vary widely in form and style, although there are several excellent examples of the classical style; the Italic-type dwellings constructed around a central atrium.

Nearby, there is the magnificent Villa dei Papiri. Dated to the mid-1st century B.C., and believed to have belonged to Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, the father in law of Julius Caesar. Numerous examples of decorative aspects of the structures, including statuary, bronze and terracotta effects, and exquisite mosaics are to be found at the National Museum in Naples.

To find out more: Timetravelrome.