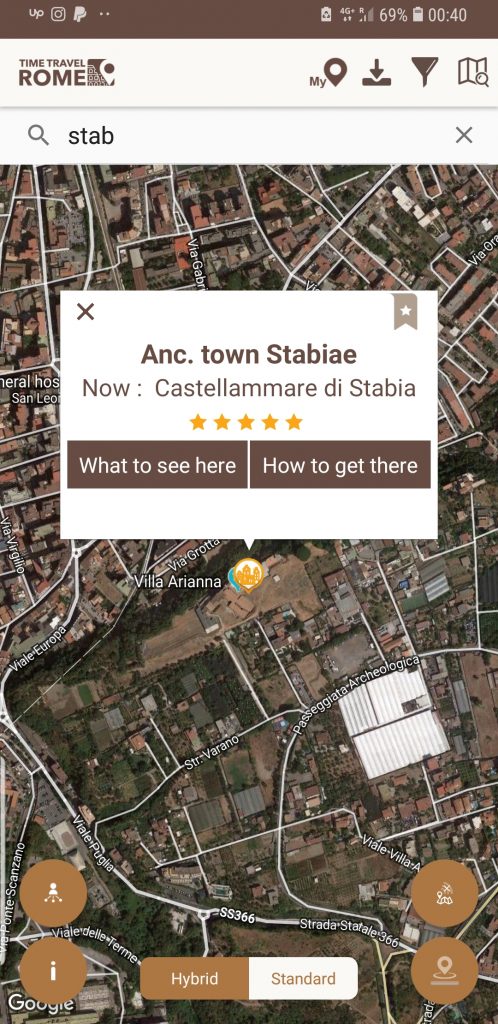

Falling rock and blocked shallows had forced Pliny the Elder and his navy from the shore at Herculaneum. Skirting the edge of the rock fall, they made their way down the coast to Stabiae, which lay south even of Pompeii. An area of numerous ornate villas, both for leisure and farm estates, it lay at the base of the peninsula. The blast from Vesuvius covered their best escape route, leaving the wealthy inhabitants terrified and trapped in Stabiae. Worse still, the wind direction stopped boats from leaving the city. It blew favorably on Pliny, however, as he arrived at the house of his friend, Pomponianus.

The House of Pomponianus

Pliny disembarked on shore and embraced Pomponianus heartily. Determined to go bravely about his normal routine in order to reassure his old friend, he asked to bathe. A little later they dined together. Pliny remained cheerful, at least outwardly, as night fell and sheets of fire were visible, leaping up from the slopes of Vesuvius. Pliny once again tried to calm his companions, insisting they were seeing abandoned campfires, or at the very least, houses already evacuated that had caught on fire. With this final assurance, he bid them all goodnight, and apparently fell into a deep sleep, for they could hear his snores through the door.

The rest of the house remained awake and restless, despite Pliny’s attempts to comfort them. Sometime in the earliest hours of the coming day, the ash had accumulated so high in the courtyard that it forced them to rouse Pliny, or risk him becoming trapped in his room. As they discussed their next move, the earth began to tremble and shake. Even the solid structure of the villa seemed to sway back and forth as it shook violently. The discussion changed from plan of action to merely whether it was safest in the building or out of it. Outside the ash and pumice stones continued to rain down, but inside seemed likely to collapse around them.

To the Shore

They made the decision to go outside, and tied pillows on their heads with strips of cloth. They needed their hands free to carry lanterns. Dawn should have been breaking, but the world was still encased in the blackness of an artificial night. Pliny led the villa residents back down toward the sea, hoping to be able to sail back to safety. Unfortunately, the waves were still high, and the wind blowing directly against them. By this time, despite his cheerful façade, Pliny was beginning to struggle. He was a stout man, and out of shape, and he struggled to breathe in the thickening air. His friend Pomponianus called for a sheet to spread on the ground, and Pliny lay down, asking frequently for cold water.

Stabiae was relatively lucky, far enough away to escape almost all of the pyroclastic surges. Only the very edge of the sixth blast reached the city, and its heat and noxious fumes were no longer enough to kill all in its path instantly. Pliny and his companions smelled Sulphur as it approached. With the premonition that something terrible was approaching, they pulled Pliny to his feet and tried to help him to flee with them.

The End of an Icon

Two of the household slaves supported him as they ran, but it was too much for him. His windpipe had been weak for years, prone to inflammation under the best of circumstances. He choked suddenly on the fumes and utterly collapsed. The household, even Pomponianus, could only run, suffused by guilt at having to abandon their friend and would-be savior. A full day and more after, the darkness dissipated, and they were able to return. They found Pliny’s body, untouched and uninjured, and appearing as if he were merely sleeping. Pliny had enjoyed an illustrious career as a politician and an eminent scholar. His book, Natural History, became a template for future encyclopedias. Sadly, many of his works, including large segments of his Natural History, remain lost.

On that terrible day in 79 A.D., back in Misenum, Pliny’s family remained unaware of his fate. His sister and nephew refused for a long time to escape without him, despite the pleas of friends, and they almost lost their own lives to the tragedy because of it.

Sources: Pliny the Younger, The Letters of the Younger Pliny, 6.16

This article was written for Time Travel Rome by Marian Vermeulen.

Photo: Villa San Marco – Atrio by Mentnafunangann is licensed under CC3.0

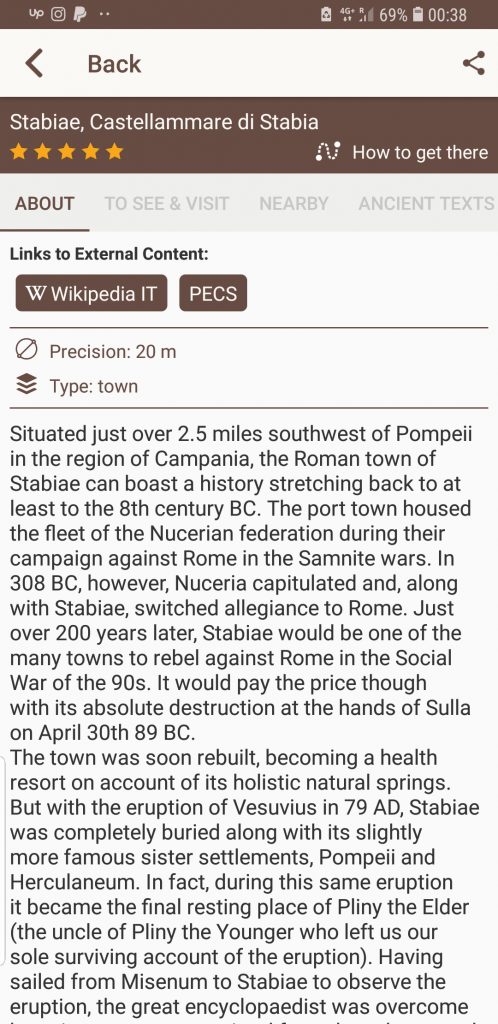

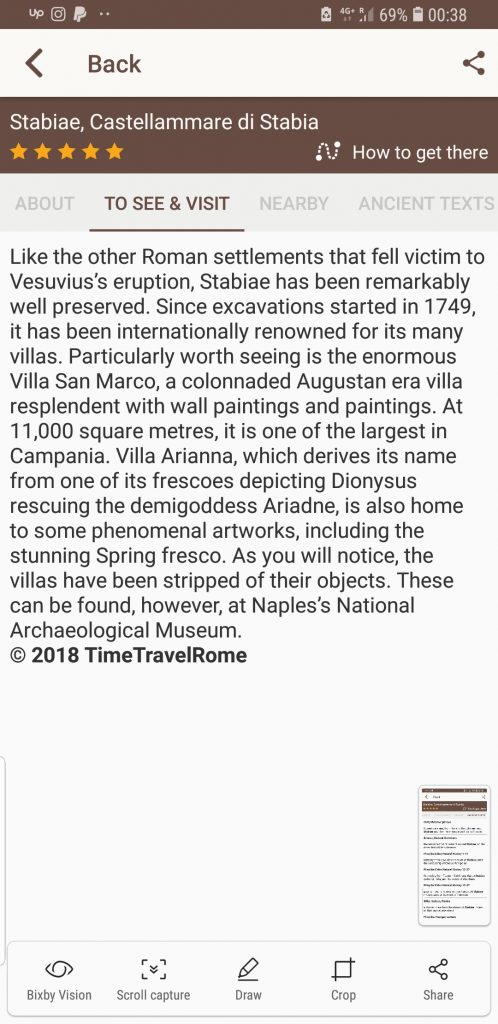

What to see there:

Like the other Roman settlements that fell victim to Vesuvius’s eruption, Stabiae has been remarkably well preserved. Since excavations started in 1749, it has been internationally renowned for its many villas. Particularly worth seeing is the enormous Villa San Marco, a colonnaded Augustan era villa resplendent with wall paintings and paintings. At 11,000 square metres, it is one of the largest in Campania. Villa Arianna, which derives its name from one of its frescoes depicting Dionysus rescuing the demigoddess Ariadne, is also home to some phenomenal artworks, including the stunning Spring fresco. As you will notice, the villas have been stripped of their objects. These can be found, however, at Naples’s National Archaeological Museum.

To find out more: Timetravelrome