“There are two wayward daughters that I have to put up with: the Roman commonwealth and Julia.”

– Emperor Augustus

Julia Augusti filia, or Julia the Elder, daughter of the Emperor Augustus, was a fascinating wild card in an era and culture where the ideal woman was quiet, steadfast, and even-tempered. Her personality was neither uniquely good nor bad, and like many famous individuals of the ancient world, reflected the innate complexities of human nature. She was kind, empathetic, intelligent, and quick-witted, while at the same time a wild partier, adulterer, and possibly even guilty of plotting patricide against a father who, despite his many flaws in parenting, loved her dearly.

Despite his devotion, accusations of her conspiracy finally forced Augustus to face all of her misdeeds. The charges would have meant execution of any other citizen, but unable to order the death of his daughter, Augustus instead exiled her to isolation in an ornate villa on the island of Pandataria. She remained under nominal house arrest until her own death, a short time after the passing of her father. Perhaps most captivating is how closely the difficult relationship between father and daughter and its results parallel modern situations, albeit amplified.

Young Julia

Augustus left his first wife, Scribonia, in 39 B.C., the very day that Julia was born, saying that he was “unable to put up with her shrewish disposition.” He took Julia away as soon as she could leave her mother, and Julia instead grew up in the house of her stepmother, Livia. She was raised in luxury and provided with the very best teachers, and subsequently she developed a deep love of literature and culture. She had a sharp mind and a quick tongue. Yet despite all the comforts of her childhood, it was also a strict and sheltered one. Augustus insisted that everything she said and did be proper, nothing that she would be ashamed to have written in the household records. He also carefully restricted their interaction with strangers. One of his letters includes an admonishment to Lucius Vinicius, “a young man of good position and character: “You have acted presumptuously in coming to Baiae to call on my daughter.”

She had been betrothed at the age of two to Mark Antony’s then ten year old son, though the later civil wars dissolved that arrangement. Still, her marriage was entirely at the will and needs of her father, and at fourteen she was wed for the first time to her cousin, Marcus Claudius Marcellus. Julia’s father was unable to attend the wedding, having fallen ill on a trip to the provinces, and instead he asked his right hand man, Marcus Agrippa, to oversee the ceremony. Marcellus was likely being groomed as a possible heir. Augustus’s only other possible successor, Agrippa, was the same age as the princeps, and a younger candidate was needed.

Many Marriages

Augustus undoubtedly also hoped that Marcellus and Julia would produce sons that he could then adopt, ensuring the future of their dynasty. Unfortunately, after only two years of marriage, Marcellus died childless. Two years later, Augustus married Julia, now eighteen years old, to Agrippa. Agrippa was around twenty-five years older than Julia, making the marriage a much more typical one than her match with Marcellus, who was very similar to her in age. Agrippa was also frequently away. Being Augustus’s top general, he was sent on campaigns in all corners of the provinces to maintain peace in the budding empire.

It was during this time that Julia began to act out. She apparently carried on several adulterous relationships, the longest of which was an affair with her “persistent paramour” Sempronius Gracchus. She is also said to have taken Iullus Antonius, second son of Mark Antony and brother of her first betrothed, as a lover, as well as lusting after Tiberius, her stepbrother. Despite her dalliances, she and Agrippa had five children together. Marcobius Theodosius recorded that on one occasion, when she was teased about the fact that it was surprising that all of her children looked like Agrippa, she quickly shot back ““I take on a passenger only when the ship’s hold is full.”

Julia even traveled extensively with Agrippa, who appears to have held affection for her despite their arranged marriage. He flew into a rage when Julia almost drown in Ilium, and laid a heavy fine on the citizens for carelessness. Only his good friend Herod had the nerve to approach him, and Agrippa listened to the plea and withdrew the fine.

Exiled to Pandataria

Shortly after returning to Italy, Julia once again became pregnant, and Agrippa fell desperately ill. He died at their villa in Campania. Julia named her son Marcus Agrippa Postumus in honor of his father. By this time, Augustus was becoming desperate for an heir. He had adopted Julia and Agrippa’s first two sons, Gaius and Lucius, but they were still quite young. Agrippa had returned to the position of expected heir after the death of Marcellus, and now he too was gone. Augustus was not a young man, and he needed an heir old enough to be able to run Rome. He quickly adopted his stepson Tiberius and immediately married Julia to him.

Despite her reported interest in Tiberius as a young girl, Julia and Tiberus’s marriage was a disaster from the outset. Tiberius had been deeply in love with his first wife, Vispania Agrippina, whom he was forced to divorce in order to marry Julia. He was also not impressed with Julia’s questionable sexual morality. Meanwhile Julia had barely finished mourning Agrippa, and considered Tiberius beneath her. They conceived one child who died as an infant and the couple separated soon after. According to the histories, Julia descended into even greater depravities at this point, and when her excesses were brought before Augustus, along with an accusation that she had joined a plot against him, he was finally forced to face the issue. Julia was banished to Pandataria, accompanied voluntarily by her mother.

Death of Julia

“After Julia was banished, he denied her the use of wine and every form of luxury, and would not allow any man, bond or free, to come near her without his permission, and then not without being informed of his stature, complexion, and even of any marks or scars upon his body.” It was not until five years later that Augustus allowed Julia to return to the mainland and to live in a villa at Rhegium. However, he could not be convinced to forgive her, despite the fact that the Roman people several times interceded on her behalf. Instead, he bitterly stated in the open assembly that if they continued to press for her release, then he “called upon the gods to curse them with like daughters and like wives.” Augustus wrote a clause into his will forbidding Julia to be buried in the Mausoleum of Augustus.

After Augustus’s death in August of 14 A.D., power passed to Tiberius. Practically at the same time as the princeps death, Agrippa Postumus was killed by a centurion named Gaius Sallustius Crispus, who then reported to Tiberius that “his orders were carried out.” Tiberius fiercely insisted that he had no involvement in the execution, yet his only real rival was now eliminated. Julia also did not survive to the end of the year. Tiberius refused to provide for her, and left her imprisoned in her villa to slowly die of destitution and possibly even starvation.

What to See in Punta Eolo now ?

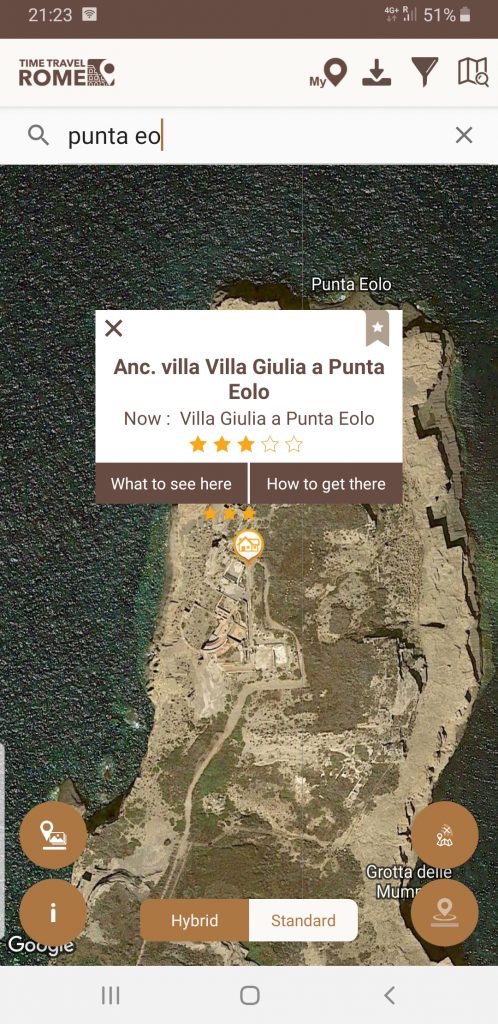

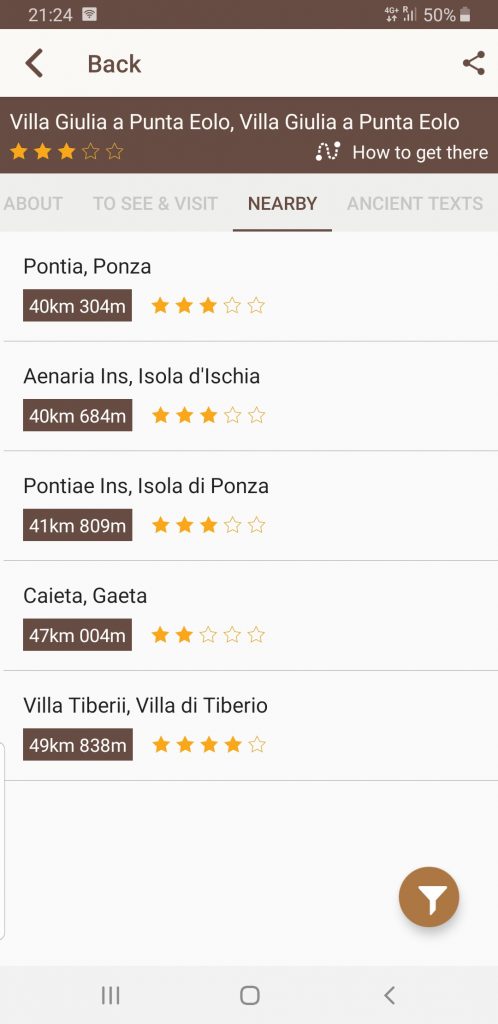

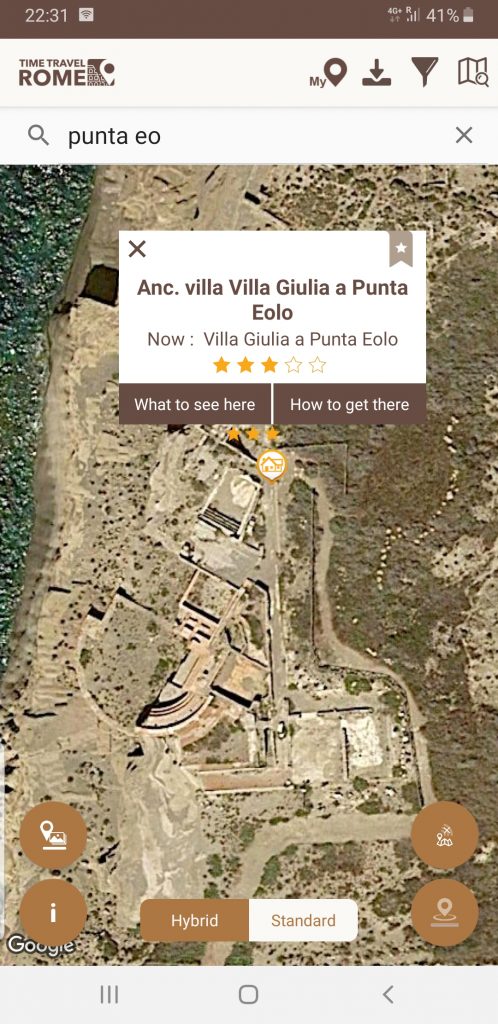

The Villa Giulia a Punta Eolo was the location on the island of Pandataria (now Ventotene) to which the emperor Augustus banished his daughter Julia the Elder in 2 B.C. Her abode on the island was a large and luxurious villa, complete with its own bath complex. It had been constructed originally as a summer residence for the emperor himself. The foundations of the villa have been excavated and the bath complex in particular is well preserved. The Museum of Ventotene also holds a number of artifacts excavated from the villa.

Julia was not the only high-ranking personage to be banished to the villa. Subsequently, in 29 AD, it accommodated Augustus’s granddaughter Agrippina after she was banished by Tiberius. She died there, allegedly starved to death, in 33 AD. Her son, the emperor Caligula, brought her remains reverently back to Rome and went on to exile his sister Julia Livilla to the villa. Julia Livilla was banished to Pandataria for a second time in 41 AD, this time on the orders of her uncle, the emperor Claudius. She too is said to have been starved to death here. Also incarcerated and then executed on Pandataria was Nero’s first wife, Claudia Ottavia.

Pandataria (Punta Eolo) on Timetravelrome App:

Sources: Cassius Dio, Roman History; Suetonius, Life of Augustus; Tacitus, The Annals; Pliny the Elder, Natural History; Velleius Paterculus, Roman History; Macrobius, Saturnalia.

Author: Marian Vermeulen for Timetravelrome

Header image: Ventotene (island), photo by Sailko licensed under CC BY 3.0