“Remember, too, on every occasion that leads you to vexation to apply this principle: not that this is a misfortune, but that to bear it nobly is good fortune.”

– Marcus Aurelius

Article written by Marian Vermeulen

Father and Son

With a shared love of philosophy, intellect, virtue, and kindness, Marcus Aurelius and Antoninus Pius were an excellent match as father and son and as emperor and heir. Marcus married Antoninus’s daughter, Faustina the Younger, and further tightened their familial ties. The new emperor also made Marcus his consular partner on a number of occasions, granted him the title of Caesar, made him one of six commanders of the equestrian order, and gave him a high position in the priesthood.

Marcus genuinely adored his adopted father, and praises him at great length in his Meditations, enumerating countless virtuous qualities. Marcus gave Antoninus his unswerving loyalty, and over the next twenty-three years, “he conducted himself in his father’s home in such a manner that [Antoninus] Pius felt more affection for him day by day, and never in all these years, save for two nights on different occasions, remained away from him.”

As the years passed and Antoninus began to slow down, Marcus took on even greater responsibility and served ostensibly as Antoninus’s co-emperor, though not named as such. Marcus was already nominally in charge of the government by March of 161 A.D. when Antoninus contracted a fever at his favorite family estate in Lorium. Marcus rushed to be at his side. He charged Marcus with the care of both his daughter Faustina and of Rome, asked his attendants to move his golden statue of Fortune from his bedside to Marcus’s, and then rolled over as if to sleep and quietly died, ending a reign of unprecedented peace in the Roman Empire.

Co-Emperors

The Senate quickly hailed Marcus as imperator, Augustus, and Pontifex Maximus, but Marcus laid out a single, imperative condition to his taking the position: his adopted brother Lucius Verus, now also betrothed to his daughter Lucilla and his future son-in-law, must be named co-emperor. It was a first for imperial Rome, but the Senate eventually agreed. It was a wise and practical decision. The Empire had grown to be a huge responsibility for a single man to manage. Additionally, Marcus had long been less active and prone to illness, and rarely traveled outside of Rome.

Yet his intelligence and character, combined with years of experience and a deep understanding of Roman politics, made him an ideal administrative and political leader. His brother was the opposite, younger, stronger, and preferring action to thought. Though he still deferred to Marcus as the senior ruler, he was perfectly suited to be the supreme commander of the Roman legions, and to coordinate Roman military endeavors far afield. Their joint rule allowed them to succeed in all arenas, and to maintain a constant imperial presence both at home and in conflicted provinces.

One Glorious Year

Having ruled alongside Antoninus for so many years, Marcus took imperial rule with experience and knowledge of his duties and of Rome that many previous emperors did not enjoy. Therefore, while Lucius energetically organized the military, Marcus earned great goodwill for his early reforms politically. He added court days to the calendar, overseeing many of the cases personally, and showing a particular interest in laws managing the protection of orphans and children, the manumission of slaves, and the choosing of city officials. He showed immense respect for the Senate, asking their opinion in may matters, coming to them personally if he wished to make a proposal, and attending every meeting if he was in Rome, even staying late into the night when elections ran long.

He was frugal with imperial funds, heavily reducing games and revising taxes, but investing instead in welfare programs to support the poor. He also required wealthy officials to invest some of their fortune back into the Roman Empire, shamed informers, and ignored attempts at bribery. He was equally temperate in his personal relationships, “at all times exceedingly reasonable both in restraining men from evil and in urging them to good, generous in rewarding and quick to forgive, thus making bad men good, and good men very good, and he even bore with unruffled temper the insolence of not a few.” Marcus and Lucius’s first year of rule was one of peace and prosperity, but misfortune waited around the corner.

Multitude of Disasters

In 162 A.D., heavy rains pushed the Tiber over its banks and flooded much of the city of Rome, causing immense damage to homes and property. The loss did not end there, however, for the flooding continued into the surrounding countryside, destroying agricultural estates, drowning numerous livestock, and plunging the city into famine. Though legislative details have not survived describing Marcus and Lucius’s actions, they are both highly praised in ancient sources for their personal investment in resolving the crisis, both in terms of their time and efforts, and large amounts of their own personal fortunes spent in mitigating the disaster.

At about the same time, the situation with the Parthians in Syria was becoming unmanageable, and Marcus sent Lucius to lead the campaign personally. It was exactly the reason for insisting on the co-emperorship in the first place, but Marcus may have had another reason. The Historia Augusta suggests that Lucius was becoming rather wild at home, and Marcus sent him to get him out of the public eye and in the hopes that he might learn some responsibility.

The Historia Augusta is prone to dramatics and this might be discounted as an embellishment except that other sources corroborate that Lucius’s behavior on route to Syria was disgraceful. He moved slowly through the provinces, enjoying their particular delights, all “while a legate was being slain, while legions were being slaughtered, while Syria meditated revolt, and the East was being devastated.” Despite his dalliances, and with the help of two excellent generals, the Parthians were defeated. The Senate granted both men high honors, and voted Lucius a triumph, which he insisted that Marcus share, the first ever triumph to honor two emperors together.

A Grievous Loss

Yet the triumph was bittersweet, for the Roman soldiers returning to Rome brought with them a plague, probably either measles or smallpox, which killed around five million people. On top of this, Germanic incursions in the north required military intervention. Whether it seemed like an incident that required two commanders or whether Lucius’s behavior had caused Marcus to lose faith that he could trust his brother alone, this time, Marcus and Lucius set out together to command the legions. However, the matter was quickly resolved for the tribes sued for peace and the brothers accepted and turned for home.

While travelling through Pannonia, Lucius became ill and eventually died in the carriage with Marcus at his side. Though Cassius Dio hinted that there was suspicion that Lucius was killed for plotting against Marcus, the claim is unsupported and largely disbelieved. Marcus mourned Lucius deeply, despite all of their differences, the brothers seemed to still hold genuine affection for one another, and nothing indicates that Lucius would have sought to assassinate his brother, or that Marcus would have reacted by having him killed. In fact, Marcus was merciful on many occasions. Even the Historia Augusta labeled the death accidental. Many modern historians believe that Lucius likely fell victim to the Antonine Plague, which was still very active at the time.

After the devastating task of burying his brother, Marcus was soon called back to Germany to deal with the dangerous Macromanni Tribe. Wars with various Germanic tribes would continue through the remainder of Marcus’s reign, many of them depicted in the exquisite triumphal column of Marcus Aurelius which survives in Rome to this day.

What to See Here now?

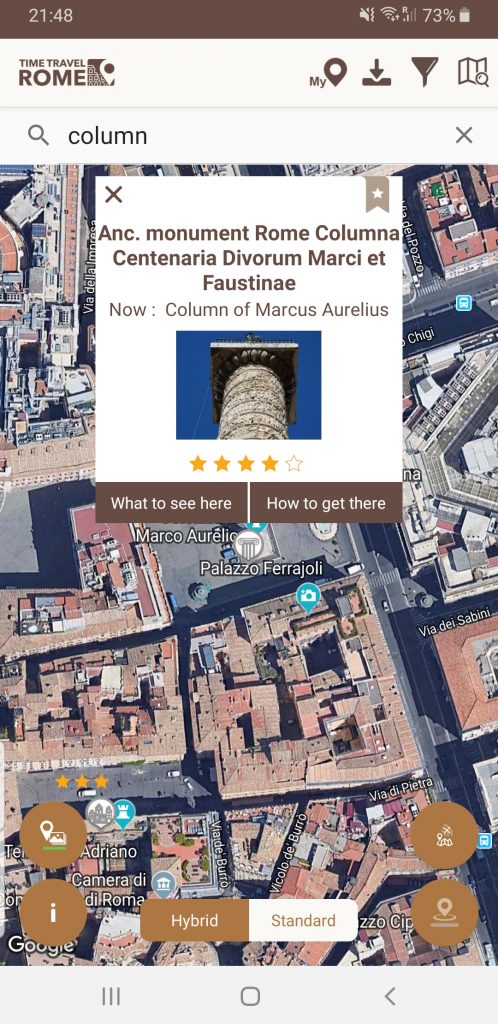

Towering above what at the time was the recently developed

area of the Campus Martius that ran parallel to the Via Flaminia, the Column of

Marcus Aurelius was erected sometime between the emperor’s death in 180 AD and

the year 193 AD. The latter date provides a terminus ante quem because of an

inscription found onsite which authorises the procurator responsible for the

column’s construction to put the monument’s wooden scaffolding towards building

his house.

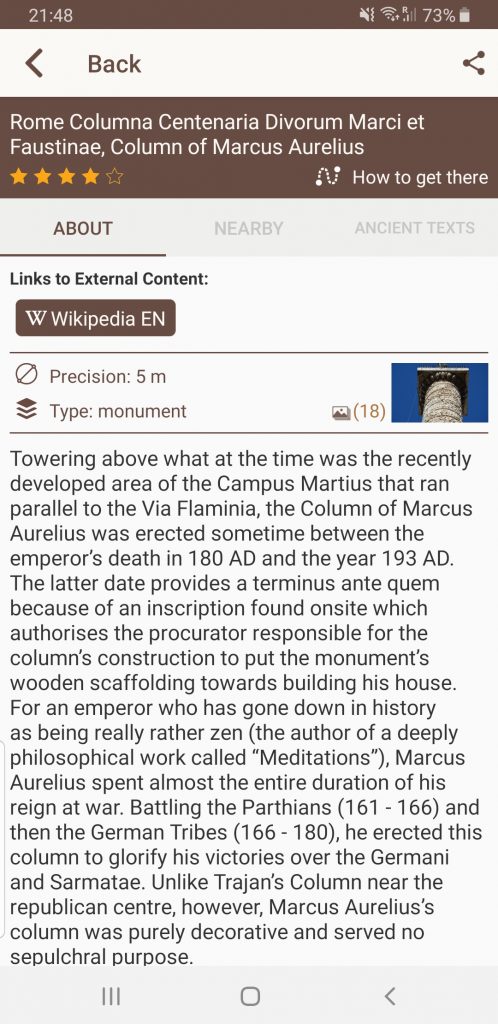

In total, the monument stands at a height of just under 42 metres. The Doric

column’s decorative relief programme is much simpler (and therefore much more

legible) than Trajan’s. It begins with the Roman army’s crossing of the Danube

before breaking off individual episodes of campaigns against the Germans. As is

the case on Trajan’s Column, Victory appears halfway through—and halfway up—to

divide the narrative between the earlier campaign (172 – 173) and the later

campaign (174 -175).

The column originally belied the modern street level by some three metres; its base decorated on three sides with festooned depictions of Victory. In all likelihood, it stood in the foreground of the Temple of the Divine Marcus Aurelius, erected by his son Commodus. Only traces of this presumably demolished temple survive. As with the case of Trajan’s Column, a spiral staircase was built into the shaft of the column, leading from the base right up to the top level.

Column of Marcus Aurelius on Timetravelrome App:

Author: Marian Vermeulen for Timetravelrome

Cassius Dio, Roman History; Marcus Aurelius, Meditations; Sextus Aurelius Victor, Epitome De Caesaribus; Historia Augusta, The Life of Antoninus Pius.

Header image: Detail from the Column of Marcus Aurelius in Rome. Photo by Barosaurus Lentus, licensed under CC BY 3.0.