Continued from the Part I.

…“So Cleopatra, taking only Apollodorus the Sicilian from among her friends, embarked in a little skiff and landed at the palace when it was already getting dark; and as it was impossible to escape notice otherwise, she stretched herself at full length inside a bed-sack, while Apollodorus tied the bed-sack up with a cord and carried it indoors to Caesar. It was by this device of Cleopatra’s, it is said, that Caesar was first captivated, for she showed herself to be a bold coquette.”

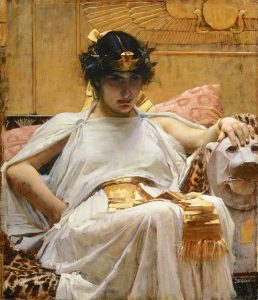

Cleopatra (1888). By John William Waterhouse (1849-1917). Public Domain.

Cleopatra remains somewhat enigmatic, despite her many appearances in ancient histories. Some historians describe her as a ravishing beauty. Others claim that she was attractive, yet not stunningly gorgeous; rather it was her confidence, intelligence, and personality that captivated the Roman men who visited Egypt. Cleopatra was fluent in at least nine languages, giving her the advantage of entertaining ambassadors and communicating with her people without using an interpreter. She was the only Pharaoh of the Ptolemaic Dynasty to learn the native Egyptian language. Her charismatic wit and charm impressed all who met her, and particularly attracted the attention of the Romans, whose usual ideal for woman was something altogether more quiet and demure.

Siege of Alexandria

Thanks to her dramatic appearance before Caesar, the Roman general agreed to take up her cause, and initially worked to reconcile her with her brother and husband, Ptolemy. It seemed successful, but the general Achillas escaped to his camp and kicked off a war with Caesar, besieging Caesar and Cleopatra, who remained in the palace of Alexandria with Ptolemy held as captive. Cleopatra’s younger sister, Arsinoe, soon arranged for the assassination of Achillas and took command of the Egyptian forces.

Outnumbered and surrounded in the city, the war was a difficult one for Cleopatra, Caesar, and his men. Arsinoe ordered the water canals filled with seawater, causing panic among Caesar’s soldiers. However, they managed to dig new wells that directly accessed fresh water and also sent ships to search for fresh water along the coast. Arsinoe next tried to cut Caesar off from his fleet, but he responded with a fire that caused significant damage to the great Library of Alexandria. Unfortunately for Arsinoe, she was betrayed by the Egyptian officers, who had little interest in being commanded by a woman. They negotiated an exchange, sending Arsinoe as a captive to Caesar and thereby securing Ptolemy’s release.

A 19th century illustration of the burning of the Library of Alexandria. Source: www.thedailybeast.com

Ptolemy maintained the siege, but eventually Mithridates of Pergamon came to the aid of the besieged Caesar and broke his forces out of the city. They met with Ptolemy’s opposing army in the Nile Delta in February of 47 B.C. The battle was fierce and hard fought, with Caesar’s forces attacking their enemy’s fortified camp. Finally, however, a contingent of the Romans managed to break through and attack Ptolemy’s forces from the rear, and the frightened army broke and scattered.

Caesar and Cleopatra

With her husband neutralized, Cleopatra emerged as the sole ruler, but she married her younger brother, Ptolemy XIV, to maintain the illusion of a male ruler. The marriage was nothing more than political theatre, and Cleopatra spent her days and nights instead with Caesar. Already a notorious womanizer in Rome, Caesar delayed in Egypt until April to enjoy his dalliance with Cleopatra, an uncharacteristic move for the ambitious general who almost never paused his military and political operations. Yet Caesar remained captivated by Cleopatra. Suetonius claims that he joined her for a cruise down the Nile on a luxury barge, viewing the monuments and buildings of Egyptian history. She also almost certainly showed him around the Mouseion of Alexandria, and introduced him to the new style of dating which Caesar would adopt as the Julian calendar, a direct antecedent to the calendar we still use today.

Julius Caesar. August 43 BC. AR Denarius. Rome mint. Laureate head right within within pelleted border / Venus Genetrix as Felicitas holding caduceus and long scepter. www.cngcoins.com Used by permission of CNG.

When he finally left Egypt for Syria, Cleopatra was heavily pregnant, and shortly after his departure, gave birth to a boy that she named Caesarion. Caesar remained publically silent regarding the child, neither claiming him as his own nor denying his parentage, but Cleopatra loudly declared Caesar as the father, and few doubted her. After his return to Rome, Caesar invited Cleopatra to join him in the capital city, an invitation which she gladly accepted, staying in Caesar’s villa in the Horti Caesaris, the Gardens of Caesar, outside the city walls. These would later be purchased by Sallust, and became known as the Gardens of Sullust.

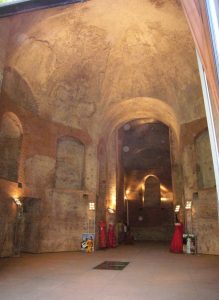

Gardens of Sallust. Photo by Lalupa, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Queen of Egypt

Cleopatra was largely despised by the Romans, seen as a foreign tramp and a potential threat. Caesar did not help this distaste by commissioning a golden statue, modeled on Cleopatra, which he placed in the Temple of Venus Genetrix. Despite her unpopularity, her presence and poise remained as striking as always, and soon Roman women were imitating her hairstyle and fashions. Cleopatra and Caesarion were still in Rome when, on March 15th of 44 B.C., a group of conspirators murdered Caesar during a meeting of the Senate.

Temple of Venus Genitrix, Forum Iulium, Rome. By Jebulon – Own work, CC0.

Cleopatra bravely remained in Rome until the reading of the will, hoping that Caesar would name Caesarion as his son. However, Caesar’s will declared his nephew, Octavius, as his sole heir. Cleopatra fled the volatile situation in Rome and returned to Egypt. Once there, she poisoned her younger brother and named her young son Caesarion as her co-ruler. She had lost Caesar and the power of his legions, but she had gained the unchallenged sole rule of Egypt.

To be continued….

The Gardens of Sallust: What to See Here?

The splendid parkland that sprawled across the valley between the Pincian Hill and Esquiline hills was first acquired by Julius Caesar in the first century BC. After the dictator’s death, the governor of Africa Nova and famous historian Sallust (author of the Catilinarian Conspiracy and Jugurthine War) purchased the property—thus giving it its enduring name—and left it to his great-nephew when he himself died in 35 BC.

Horti Sallustiani, Aula Adrianea. By Lalupa – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

In 20 AD, the gardens passed into the hands of the Emperor Tiberius and where henceforth kept and maintained by various successive Roman emperors as part of the Imperial property. Vespasian, the first of the Flavian emperors, certainly enjoyed staying there; presumably the fact it was in these very gardens that his army had fought the decisive battle that won him control of the city did nothing to keep him up at night. Nerva, the first of the following dynasty, loved them too: the gardens being the spot where he shuffled off his mortal coil in 98 AD.

View of the interior of the ruins of the Temple of Venus in the Gardens of Sallust, Rome, with four figures Etching. Engraving by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, from Varie vedute di Roma antica e moderna (Various Views of Ancient and Modern Rome), published by Fausto Amidei, 1748. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The Gardens of Sallust were expanded under Hadrian and Aurelian; the latter, according to the Historia Augusta, adding a mile-long portico along which he would regularly ride his horse. The gardens’ beauty couldn’t save it from destruction in the fifth century however, and the gardens and its monuments were finally sacked by Alaric and his Goths in 410 after their entry into the city through the gardens’ gates.

Time has not been kind to the Gardens of Sallust. Rome’s expansion in 1871, as the capital of the Republic of Italy, saw much of the valley between the Pincio and Quirinal filled in, burying whatever had survived centuries of sackings, fires, earthquakes and destructive construction (or reconstruction) projects. Nothing survives of Aurelian’s mile long portico, nor can we find any remains of the sepulchre erected to house the bodies of two Augustan giants who apparently measured a staggering 10’3.

Sallust Gardens in Rome. By Carlo Dani – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.

There are some hints of the gardens’ former glory however. The well-preserved remains of a three-storey pavilion, buried some 14 metres underground, can be seen in the centre of the modern Piazza Sallustio. A Hadrianic cistern is situated at the corner of Via San Nicola da Tolentino and Via Bissolati. And a cryptoporticus that probably dates from the third century AD is still visible from the garage of the nearby United States Embassy.

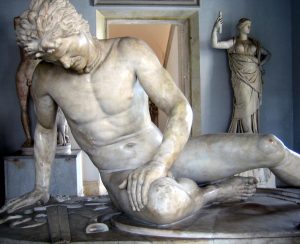

Though the Gardens of Sallust have fared badly, certain treasures recovered from them still survive spread out across the city. The obelisk that now stands at the top of the Spanish Steps was first erected in the Gardens of Sallust sometime after the death of Augustus. Likewise, the statue of the Dying Gaul now housed in the Capitoline Museums was taken from the gardens and dates from the time of Julius Caesar.

Dying Gaul – Palazzo Nuovo – Musei Capitolini, Rome. Copy after Epigonos, CC BY 2.0.

Silenus holding the child Dionysos. Marble, Roman copy of the 1st–2nd century CE after a Greek original of the late 4th century BC. Now in Louvre, France. From the Horti Sallustiani in Rome. Photo by Jastrow, Public Domain.

Gardens of Sallust on Timetravelrome App:

Timetravelrome offers an extensive coverage of monuments in Rome. 195 ancient sites of Rome are precisely placed on the map, illustrated and described in detail.

Sources: Plutarch, Life of Caesar; Cassius Dio, Roman History; Appian, Civil Wars; Caesar, African Wars; Suetonius, Life of Caesar

Featured image: “Caesar giving Cleopatra the Throne of Egypt” by Pietro da Cortona. Public Domain.