Michel Gybels for Time Travel Rome

Curinga is a small village near Catanzaro in Calabria. The Calabrian area has always been an inexhaustible source of archaeological finds, especially in a well-demarcated area known as the Isthmus of Mercellinara: a narrow strip of land separating the Ionian Sea from the Tyrrhenian Sea. The Roman thermal baths of Acconia di Curinga are situated near the center of the village on a small rural road and the visit is free. They are supposed to be private baths that were part of a large monumental villa, belonging to a very powerful family. Situated near the via Popilia, which led from Rome to Reggio Calabria, Curinga Roman Baths it is the only example of the use of Roman Africa’s construction techniques in Italy

Map of the Via Popilia. Public Domain

History of the Complex

The thermal complex of Acconia di Curinga is situated in the alluvial plain, shaped by the estuaries of Amato and Angitola rivers, in a very populated region since the Roman times.

Acconia region and Curinga on the Map of the Isthmus of Marcellinara. Source: Openstreetmap

The complex was built during the Imperial era and features various rooms like the frigidarium, the tepidarium and caldarium. The building, wrongly identified in ancient literature as the temple of Castor and Pollux, underwent scientific examination only from the 1960s onwards.

Appearance of the Curinga site in the 1960’s, before the excavations. Source: Klearchos magazine, 1966.

The discovered materials and analyzed masonry techniques corroborate the thesis that the baths were refurbished between the 3rd and the 4th century, and the monument remained in use until the end of the 6th century, serving different purposes.

View on the Baths complex. Photo by Michel Gybels.

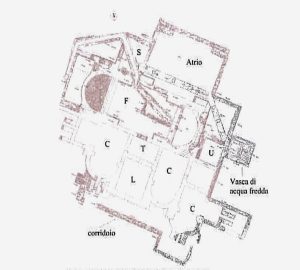

The Archaeological Survey

The visible parts of the complex occupy an area of about 1000 square meters, even if preliminary investigations suggest a planimetric development, and thus land occupation, of at least twice as much. The structure consists of service and utility rooms. The first ones are located on the south-eastern side and are overall six praefurnia, functional to heating air and water. The second ones, starting from the South to the North are caldaria (marked by the letter “C” on the plan below), tepidaria (letter “T”), and a frigidarium (F). A rectangular room, interpreted until today as an atrium or gymnasium (“Atria” on the plan), could correspond to a natatio, according to new excavations. In the almost symmetrical layout, one could distinguish the rooms used by women from those used by men.

Plan of the Curinga Baths. Source: Intervento di valorizzazione e tutela delle Terme Romane di Curinga.

The Rooms

The entrance to the baths was probably on the northern side, where the last excavation campaign revealed several wall structures with an uncertain function. The frigidarium is the largest room in the baths, it has a rectangular shape and it includes two large exedras. The roof consisted of a wide central cross vault, ending with two arches set on quadrangular pillars that connected the space with the two exedras, covered by small domes. The internal face of the walls of the exedras were interrupted by three semicircular niches, carved into the masonry, that probably hosted some statues.

The view on the exedra of the frigidarium from the exterior of the Baths. Photo by Michel Gybels.

From the frigidarium there was an access to a small rectangular room, surrounded on three sides by other spaces: it was a tepidarium, in which acclimatization to the higher temperatures took place. It constituted, both functionally and architecturally, the connecting element between the frigidarium and the rest of the baths complex. Given the state of preservation of the building, bathing paths, related to the functions of each hall, can only be proposed as a hypothesis. The latest excavations have revealed a series of pillars that may belong to the peristyle of a probable gymnasium. The service rooms are all located on the southern and south-eastern side of the building.

A rectangular structure formerly believed to be a gymnasium is probably a pool – a natatio. Photo by Michel Gybels.

On the South side there is a corridor, which allowed the loading of the pre-sufornia for the southern basins of the calidaria. The corridor was accessible through a door on the western side of the wall with three steps, which make it clear that these rooms were located below the floor levels and away from the view of those who used the structure. The corridor has a well-preserved cobblestone pavement.

View on the southern part of the Baths complex. Photo by Michel Gybels.

Building Technique

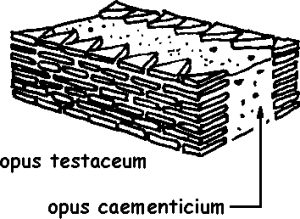

The building technique that characterizes the first phase of the building is opus testaceum, as face of the wall structures. The bricks used in Curinga are between 3.5 and 4 cm high, varying in colour from bright red to yellow and alternating with mortar. A disastrous event affected the thermal complex in ancient times.

Example of the Opus Testaceum.

This is testified by a massive restoration intervention, both structural and conservative, characterized by a new type of building technique. That was a wall made of horizontal lithic elements alternating with bricks that were probably re-used.

The later wall re-built in opus vittatum using bricks and stones .

Another restoration of the baths, occurred in the 3rd and 4th century, was aimed at the structural reinforcement of the apse of the east caldarium, which was replaced by a curvilinear wall. Between the middle of the 4th century and the beginning of the 5th century the thermal complex was disused and lost its function.

Conclusion

The construction of the thermal complex of Acconia di Curinga is part of a lively construction activity around the middle of the 2nd century. Its presence is also confirmed by the contemporary structures found in the Roman neighborhood of Santa Aloe in the nearby city of Vibo Valentia, an area where archaeological investigations have shown the presence of building facilities together with bath facilities, attributable to the middle of the 2nd century. It is still unclear whether the baths were public or private. Probably they were part of a private villa, but other hypotheses reveal that the thermal baths could be connected to a public building.

Gone into disuse probably for the extinction of the family that owned it, the structure was transformed during the first half of the sixth century and it was used as a place of Christian worship. The building, especially the frigidarium, well suited as a place of worship for the presence of pools that could be used as baptismal fonts.

Bibliography

MEDRI M. – PIZZO A. (a cura di), Le terme pubbliche nell’Italia romana (II secolo a.C. – fine IV d.C). Architettura, tecnologia e società, Seminario Internazionale di Studio, Roma 4-5 Ottobre 2018, Roma 2019

CESAREO C.N., Le Terme Romane di Acconia di Curinga (IV sec. d.C.). Sintesi di bellezza e ingegneria, in «Lamezia Storica», numero 1, Agosto 2022