Over the past year, archaeologists and heritage professionals from the UK, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands have been working together on the “Bridging the North Sea” project. Their aim? To uncover how the North Sea connected these regions during Roman times rather than dividing them. The results are gradually showing how the sea served as a dynamic highway linking communities, ideas, and economies nearly 2,000 years ago.

Our friend and TimeTravel Rome author Michel Gybels has been involved in this collaborative effort since its launch – you might remember our post about the project kickoff one year ago. Now, we’re excited to share the key achievements from their research, highlighted in the report called “The Roman North Sea Region – A Resource Assessment and Research Questions“, released in December 2024. More information can be found on the website of the project: https://bridgingthenorthsea.org

Header page of the Report, Dec 2024

Project Scope: A Network Across the Waters

The project looked at how the Roman Empire used the North Sea and Channel coastlines to create an interconnected world of trade, military power, and cultural exchange. The research covers roughly 55 BCE (when Julius Caesar first crossed to Britain) to around 410 CE (when Roman rule in Britain ended).

What’s different about this project is its cross-border approach. Instead of studying these coastal regions separately, researchers have combined their knowledge to see how sites across four modern countries once functioned as parts of a single, complex maritime network. Some of the key highlights of this unique work are summarized below.

The Roman Coastal Landscape

The coastline during Roman times was dramatically different from today. In many places, what is now dry land was once open water, while other areas now underwater were once thriving settlements.

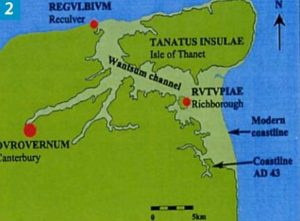

For instance, the Wantsum Channel in Kent once separated the Isle of Thanet from mainland Britain, creating a navigable waterway that Roman ships used regularly. Archaeological evidence shows that Richborough, at the southern end of this channel, served as a major port of entry and supply base. Today, this ancient seaway lies buried beneath agricultural fields, its course marked by earthen sea walls and drainage channels.

The Wantsum Channel at time of the Romans. P 135 of the Report, Dec 2024.

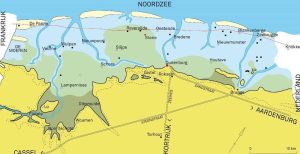

Similarly, in what is now Flanders, the coastline has retreated significantly. The Roman coastal fort of Oudenburg, which once overlooked the sea, now sits over 8 kilometers inland. This dramatic change highlights how dynamic these coastal environments were and the challenges they posed to Roman engineers and sailors.

Schematic reconstruction of the coastal plain during the mid-Roman period. Red line: the current coastline; black line: border of the coastal plain in the Roman period. P 20 of the Report, Dec 2024.

Military Infrastructure

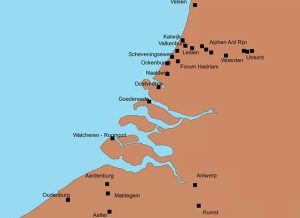

The project has documented a network of forts, harbors, and lighthouses that allowed Rome to maintain control over this maritime frontier. These installations weren’t randomly placed but formed a coherent defensive and logistical system.

Confirmed and possible Roman military installations along the coast of the Netherlands, Belgium and France. P 37 of the Report, Dec 2024.

At Dover (Portus Dubris), traces of harbor works, two lighthouses, and a fort of the Classis Britannica (British Fleet) reveal how the Romans engineered this natural harbor for military and trade purposes. Across the water at Boulogne-sur-Mer (Gesoriacum), a similar arrangement with lighthouses and a substantial harbor installation mirrors the setup at Dover, emphasizing the importance of the Dover Strait crossing.

Dover Castle and the Roman Lighthouse, By Michael Coppins – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Further north, at South Shields (Arbeia) near the mouth of the River Tyne, a fort was specially redesigned around 198 CE to serve as a supply base for Hadrian’s Wall, with numerous granaries for storing goods delivered by sea. The project has highlighted how these coastal installations were integral to the functioning of Hadrian’s Wall, connecting this frontier to the wider imperial supply network.

Material Culture: The Goods That Moved

Perhaps the most tangible evidence of connectivity comes from the artifacts that were transported across the North Sea. The project’s analysis of material culture has revealed shifting patterns of exchange that reflect broader historical developments.

During the early Roman period (43-165 CE), large quantities of pottery, especially terra sigillata tableware from southern Gaul, were imported into Britain. Metal goods, coins, olive oil in amphorae, and wine also crossed the Channel in considerable volumes. The Pudding Pan Rock site off the Kent coast, where hundreds of pottery vessels have been recovered from what may be multiple shipwrecks, exemplifies this busy trade.

Group of Roman samian ware pottery from Pudding Pan Rock. Source: Ashmolean Museum.

Interestingly, the research shows that the volume of cross-Channel exchange declined significantly after the mid-2nd century, possibly due to the combined effects of the Antonine Plague (165-180 CE) and the Marcomannic Wars that destabilized parts of the empire. At the same time, however, there was an increase in Roman goods moving into the northern Netherlands, suggesting that imperial subsidies paid to Germanic tribes were reshaping trade networks.

By the late Roman period (260-409 CE), the nature of cross-Channel exchange had fundamentally changed. Britain was exporting agricultural products to supply the Rhine legions, while importing far fewer manufactured goods. This shift from a consumer to a producer reflects the evolving economic role of Britain within the empire.

The Human Factor: Travelers Across the Sea

Beyond the infrastructure and artifacts, the project has begun to identify individuals who traveled across the North Sea, putting human faces to this maritime connectivity. Inscriptions, tombstones, and written records preserve the names of merchants, soldiers, officials, and others who made these journeys.

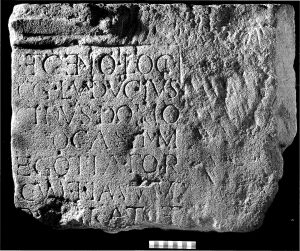

One notable example is L. Viducius Placidus, a merchant from the Rouen area in France, who is known from inscriptions both at Domburg in the Netherlands and at York in Britain, where he constructed an arch and temple. Such evidence demonstrates that individual businesspeople could operate across multiple provinces, maintaining networks that spanned the North Sea.

Dedicatory inscription made in York by Lucius Viducius Placidus. Source: https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/3195

Military personnel were also frequently on the move. A tombstone at South Shields commemorates Regina, a British woman who had married Barates, a merchant from Palmyra in Syria. Another records Victor, a Moorish tribesman who had traveled from North Africa to serve in the Roman forces in northern Britain.

These personal stories bring to life the cosmopolitan nature of the Roman North Sea world, where people from across the empire might meet and interact in bustling ports and frontier settlements.

A Landscape Under Threat

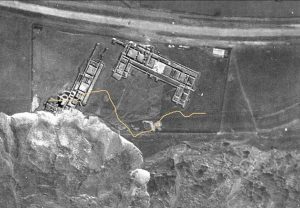

Many Roman coastal sites are now threatened by modern coastal processes and climate change. At East Wear Bay in Folkestone, a Roman villa site continues to erode as the cliff face retreats. At Reculver on the north Kent coast, much of the Roman fort has already been lost to the sea.

The Roman villa at East Wear Bay in the 1940s. The yellow line represents the current cliff edge which is progressing northwards. P 141 of the Report, Dec 2024.

In the Medway estuary, Roman industrial sites on low-lying islands are being submerged as sea levels rise, while in the Netherlands, several coastal forts have entirely disappeared beneath the waves due to coastal erosion. The project is highlighting the urgent need to document these vulnerable sites before they are lost forever.

Looking Forward: Future Research Directions

As the “Bridging the North Sea” project moves into its second year, several key research priorities have emerged:

- Developing better mapping of Roman coastal landscapes: Creating GIS-based maps that can evolve as understanding improves

- Synthesizing fragmented research: Bringing together the results of numerous small-scale investigations to build a comprehensive picture

- Fostering cross-disciplinary collaboration: Working with geologists, climate scientists, and maritime specialists to understand the ancient North Sea environment

- Sharing methodologies: Developing approaches to investigate difficult-to-access Roman landscapes that lie buried or submerged

- Building international collaboration: Strengthening networks across the North Sea to address shared research questions

One interesting proposal is for a “flagship” experimental archaeology project that would involve constructing a Roman-era vessel, potentially with teams working on different sides of the North Sea. Such a project could provide valuable insights into the capabilities of Roman ships while engaging the public across the region.

The Untold Stories of Industry: Salt, Pottery, and More

One area that deserves more attention is the industrial activities that took place along these Roman coastlines. The project has begun to document how the Romans exploited coastal resources to fuel their economy, particularly in industries like salt production and pottery manufacturing.

In Kent, over 60 Roman salt-manufacturing sites have been identified, particularly concentrated in the north and north-west of the county. These salt works were strategically positioned to take advantage of tidal flows and sea access for transportation. The production process involved evaporating seawater in large clay containers (briquetage) over hearths, creating mounds of industrial waste that are still visible in some marshland areas.

Similarly, the project has identified more than 50 pottery manufacturing sites in Kent, many located in the north Kent marshes where they could benefit from both the necessary raw materials and easy access to water transport. Black Burnished Ware, produced in large quantities along both sides of the Thames Estuary from the mid-2nd to mid-3rd century, represents one of the major pottery industries. These vessels were widely distributed, including to Hadrian’s Wall, suggesting they may have been used to transport salt or other goods.

Map of Roman Kent showing the location of key sites. P.16 of the Report, Dec 2024.

In Flanders, salt-making was also of considerable economic importance during the Roman period. Finds of briquetage pottery indicate that salt was being produced at several locations spread throughout the coastal plain, always near active tidal inlets. Recent research has shown that the salt industry evolved from small-scale household production to a more industrial scale operation using batteries of up to 15 simultaneously operating furnaces.

The economic networks that supported these industries were complex. Salt was a valuable commodity, essential for food preservation and likely traded widely. Pottery production sites like those at East Chalk near Gravesend seem to have been entire settlements dedicated to manufacturing, with multiple kilns operating alongside domestic structures and small cemeteries.

These industrial landscapes represent an important aspect of North Sea connectivity. The products made in these coastal workshops traveled far and wide through Roman trading networks, while the technologies and skills needed for these industries may have crossed the sea with specialist workers. Studying these industries gives us a different perspective on connectivity – not just of elites and military forces, but of everyday economic life and the movement of essential commodities.

A Connected Past, A Connected Future

The “Bridging the North Sea” project reminds us that the divisions between countries that seem so natural today are relatively recent constructs. For the Romans, the North Sea was not a barrier but a highway that connected regions now split between four modern nations.

By studying this shared maritime heritage collaboratively, the project is not only enhancing our understanding of the past but also strengthening international connections in the present. As research continues, we can expect even more insights into how the Roman Empire created one of the first truly integrated North Sea regions, establishing patterns of connectivity that, in many ways, continue to shape the area today.

This ancient maritime network, with its ports, forts, ships, and travelers, represents an important chapter in the history of North Sea connectivity—one that resonates with our modern world of international trade and cross-border collaboration.

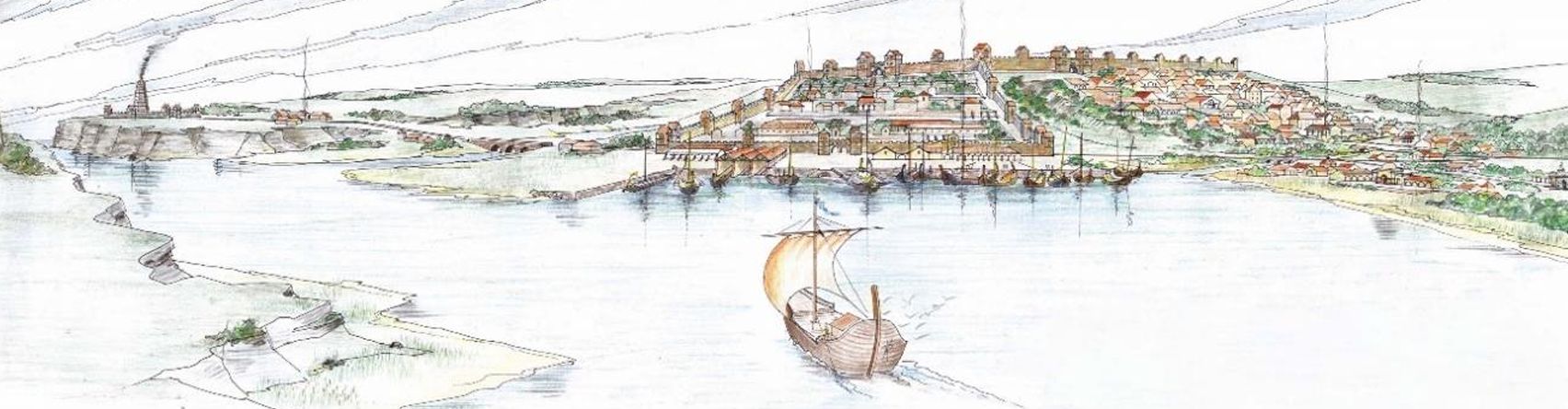

Source of the featured image: Artist’s impression: the port of Boulogne and the estuary in the 2nd century Cl. Seillier and P. Knoblock (2004) – archives of the archaeology service. Page 158 of the Report.