Right in the very heart of London, amidst the hustle and bustle of banks and businesses and the incessant rattle of the underground rails, an ancient mystery cult once convened to worship their god. This is the story of London’s Mithraeum.

The Curious Case of Ancient Londinium’s Underground God

Today, London is the UK’s largest city. Two thousand years ago, the situation was very much the same. After the original settlement had been razed in 60/61 AD during the revolt of Boudicca and the Iceni tribe, it was swiftly rebuilt as a planned Roman town. This meant the new site adhered to the typical orthogonal urban formation of a central forum space surrounded by grids of ordered streets. Prior to Boudicca’s revolt, ancient Londinium was already beginning to prosper as the historian Tacitus makes clear, describing it as:

“a busy centre, chiefly through its crowd of merchants and stores.” (1)

The Thames allowed the newly restored city to flourish, attracting people, goods, and money. Londinium expanded rapidly during this period, and by the end of the 1st century AD historians now estimate that as many as 60,000 people may have been living in the city. By the second century, when the Empire was enjoying its “Golden Age” under the auspicious rule of the “good” Antonine emperors, the ancient city of Londinium was at its zenith. It had replaced Camulodunum (Colchester) as the capital of the Province of Britannia, whilst its urban features reflected its stature. The Forum and the Basilica were the largest structures north of the Alps at the time of the Emperor Hadrian’s visit in 122 AD. Visitors to the Museum of London can see excellent displays to give a sense of the impressive scale and wealth of the ancient city, as well as a whole host of the archaeological finds made. The latter years of the 2nd century were not kind to the city however. A plague, connected to the well-known Antonine plague recorded by Cassius Dio amongst others in the western half of the empire, is believed to have been responsible for a significant reduction in population, bringing an end to the expansion of the city.

The turn of the 3rd century saw Londinium, like many places across the Empire, begin to go on the defensive. It was during the years 190-225 AD that the enormous defensive wall – known today as the London Wall, fragments of which visitors can still today – was built to protect the city. It was also at this time that the prestige of the city took a knock. The Emperor Septimius Severus, having seen off three other rivals to the throne, reorganised the provinces of the empire, including the division of Britain into Upper and Lower halves. Whilst Londinium remained the primary city of Lower Britannia, the Province of Upper Britannia was controlled by the new governor based in Eboracum (York). Despite the slight to its status, Londinium actually enjoyed something of a boost. The campaigns of Septimius Severus in Caledonia, in the far north of Britain, brought an influx of wealth into the country and Londinium benefitted with a spate of new construction works.

As well as the spate of new wealth, the armies of Severus likely brought with them new ideas and new beliefs. Just as it is today, ancient Londinium would have reflected the cosmopolitan nature of the Empire at large as cultures mingled freely. This was most clear in the religious practices and gods worshipped in the ancient city. Alongside the traditional deities of the Roman pantheon, such as Jupiter, Juno and Minerva, a host of deities from the edges of Empire also found willing devotees here. It was during the middle of the 3rd century, that the eastern mystery cult of Mithras arrived in Londinium, likely in the hearts and minds of the soldiers passing through the city on their way to the north of the island.

The Mysterious Mithras

Head of Mithras in Phrygian cap (now in the Museum of London) by Carole Raddato licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

With his distinctive pointed Phrygian cap, Mithras is arguably the most well-known of the mystery cults that existed in the Roman Empire. Their secretive underground temples, known as Mithraea, have been found across the entire expanse of the empire, including within the imperial capital itself, from Eboracum in the north of Britain, through to Numidia in North Africa and Roman Syria on the eastern fringes of the empire.

As the term “Mystery Cult” suggests, the exact nature of Mithraism remains shrouded in conjecture and is the subject of much debate amongst historians and archaeologists. The plethora of sites from across the empire have returned a wealth of material related to the practice of the cult, but there is, as yet, not written narrative or theology to have been discovered in connection with Mithraism. This significantly problematises the interpretation of the material remains.

That being said, there are iconographic consistencies. The image most commonly associated with the cult of Mithras is the Tauroctony scene. In every Mithraeum, this image of Mithras slaying a sacred bull appears to have been the centre piece. There is no formulaic style for this scene’s presentation; the image can either be carved free-standing or in relief, and sometimes appears as a fresco painting instead. However, there the typical features that are consistent across the various media. Depicted in a cave, on which the subterranean Mithraea were modelled, Mithras is depicted in typical Anatolian costume, complete with the iconic Phrygian cap, holding the head of the bull back whilst cutting its throat. Elsewhere, one can usually see the god Sol, towards whom Mithras is normally looking, along with a dog and a snake and a scorpion who is pinching the testicles of the bull.

A God Underground

In 1954, the city of London was still recovering from the ravages of the Second World War. Swathes of the city had been reduced to rubble and reconstruction was high on the list of priorities. It was against this backdrop that the then director of the museum of London, W. F. Grimes, along with his colleague Audrey Williams, happened upon the discovery of an ancient Mithraeum in the heart of the UK capital. When they first happened upon the Mithraeum, the excavators had hoped that they had found an early Christian church. However, the other archaeological remains, including a range of marble likenesses of Roman deities such as Minerva, Mercury, as well as Mithras himself, found at the site soon proved this identification untenable.

Robert Hitchman, picture available on the Museum of London Archaeology website.

Excavations in the area of Walbrook in the late 19th century had also returned a wealth of material that was likely associated with the Mithraeum as well. These included the Tauroctony relief, which includes a dedicatory inscription. Still in relatively good condition, one can see this relief and inscription today at the Museum of London – its picture is used for the header of this post.

One is able to identify all of the usual figures associated with the cult of Mithras. These include the cosmic characters, such as Sol and Luna (the Sun and the Moon) in the upper corners, along with the zodiac signs that adorn the circular band that surrounds the central scene. The inscription records the following:

ULPIUS SILVANNUS EMERITUS LEG II AUG VOTUM SOLVIT FACTUS ARAVSIONE

Ulpius Silvanus, emeritus of the Second Legion Augusta, paid his vow; enlisted at Orange (2)

The close relationship between the cult of Mithras and the soldiers of the empire are confirmed by this inscription.

Mithras on the Move

London’s Mithras can stake an unusual claim to fame for being the most mobile of the ancient gods in Britain. The Mithraeum has been moved not once, but as many as four times!

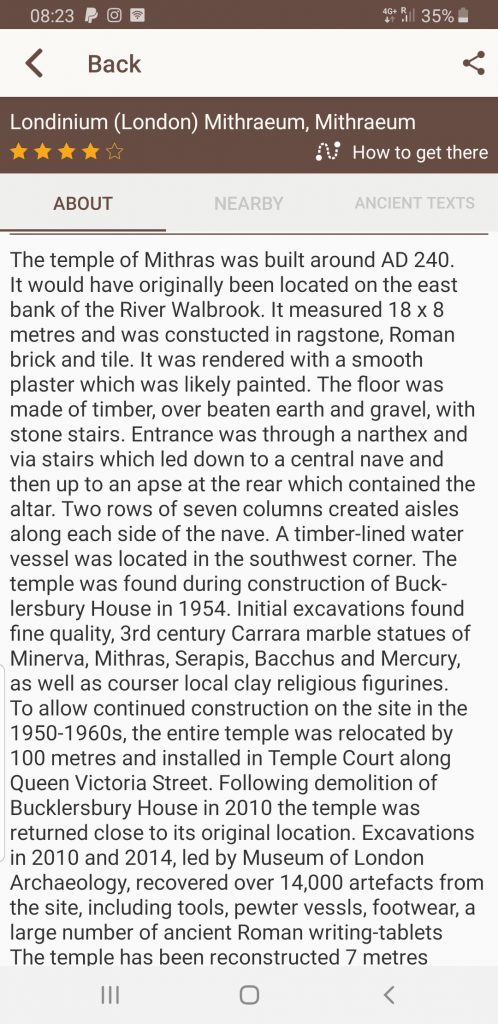

The original Mithraeum, which is believed to have been built ca.240 AD, would have stood, partially underground, on the eastern banks of the River Walbrook (a vital fresh water source in ancient Londinium which is now unfortunately subterranean). When Grimes and Williams happened across it in the 1950’s, they were left in a quandary – the site was being worked on for the construction of a modern office block, as part of London’s post-second world war recovery. Whilst debates trundled on over what to do with this remarkable archaeological discovery, the Mithraeum – having been disassembled and moved – sat in storage in a London builder’s yard for 8 years! Thankfully, a decision was reached to provide the public access to the site. The Mithraeum was rebuilt in 1962 almost 100 metres away from its original position to Temple Court. The smaller material associated with the sanctuary – including the head of Mithras and the other deities – were sent to the Museum of London. However, in a great loss to the archaeological record, the original timber benches from the Mithraeum, a tremendous rarity, were thrown away. Unfortunately, the reconstruction efforts were also met a largely negative reception, prompting accusations of inaccuracy amongst other criticisms relating to the use of modern materials to “fill-in the gaps”.

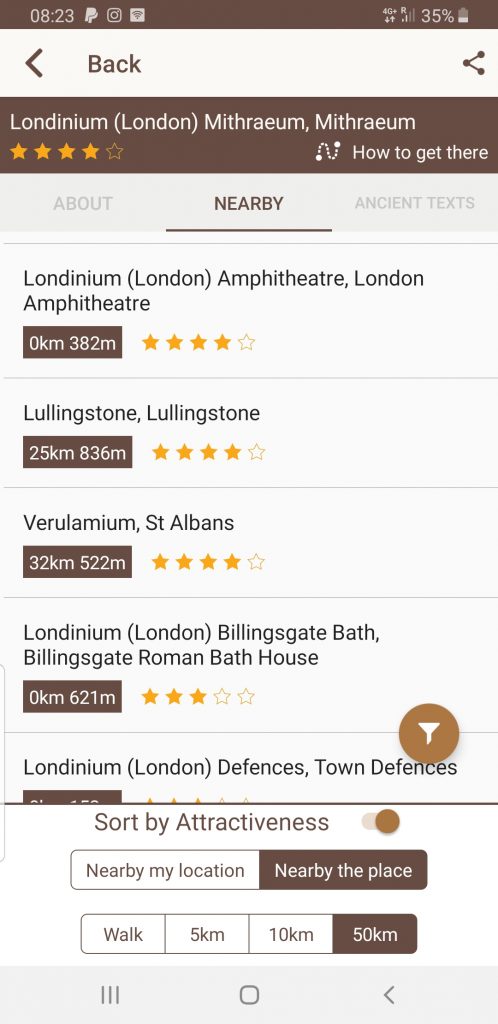

Today, the Mithraeum has moved once again. Fortunately for visitors to London now, however, the newly reconstructed sanctuary is one of the British capitals best ancient attractions. The Mithraeum has been re-moved back to its original location and is now part of the Bloomberg Company’s European Headquarters. Entrance to the Mithraeum is now free, and visitors must descend 7 meters below the modern street level to reach the reconstructed sanctuary: Mithras has been returned to his original subterranean setting. The reconstruction itself is much better than the earlier attempts in the 1960s. The recent efforts have used the original excavation reports from 1954 to produce an accurate reconstruction of the temple as it would have appeared in 240 AD, whilst the use of modern materials has been deliberately limited. Where new material has been essential, they are based on other structures from Roman Londinium. Visitors to the Mithraeum can also enjoy exploring some 600 archaeological items, all recovered from the site, that are now beautifully displayed here. Keep a keen eye out for a small wooden tablet, which records the oldest known instance of a financial transaction in Britain, dated to 57 AD, fittingly returned to the centre of the modern country’s financial sector.

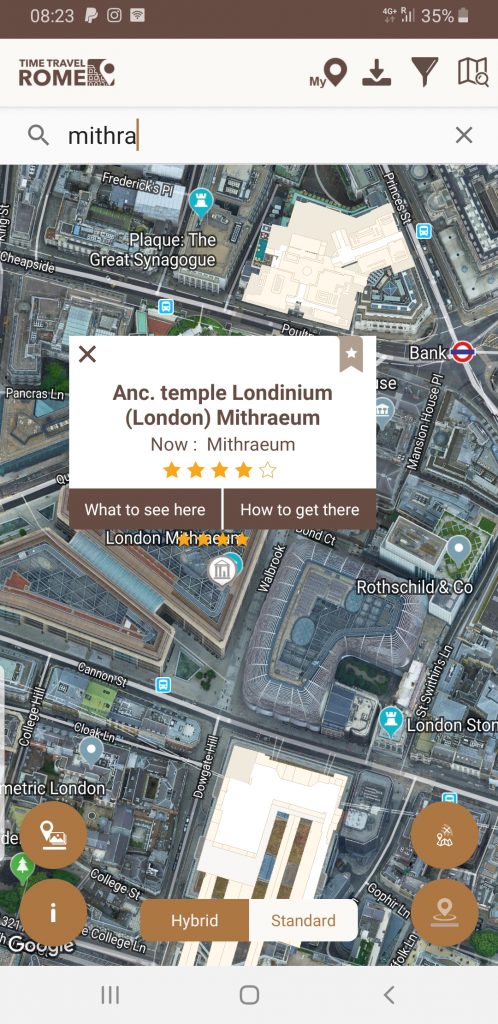

Londinium and London’s Mithraeum on Timetravelrome app:

To find out more: Timetravelrome.

Author: written for Timetravelrome by Kieren Johns.

Sources: (1) Tacitus, Annals, 33.1 ; (2) RIB 3

Header Photo: The central medallion with a bull-slaying scene, by Carole Raddato licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0