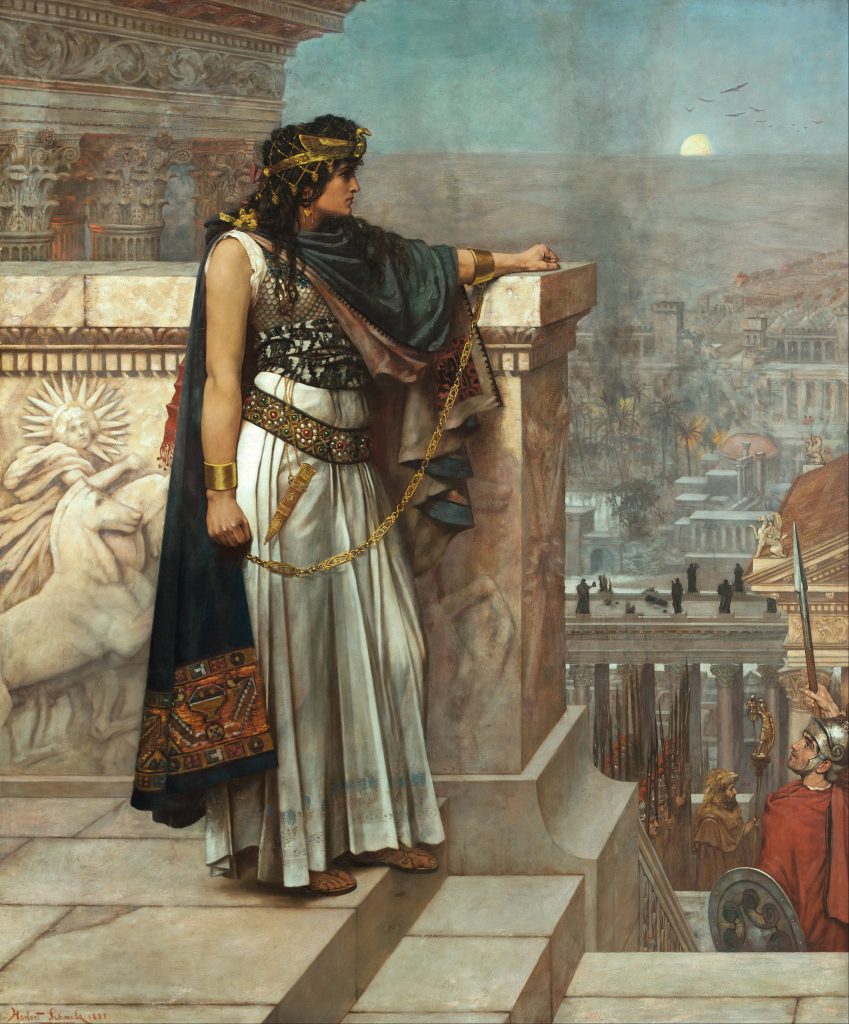

“Whatever must be accomplished in matters of war must be done by valor alone. You demand my surrender as though you were not aware that Cleopatra preferred to die a Queen rather than remain alive.”

– Zenobia to Emperor Aurelian

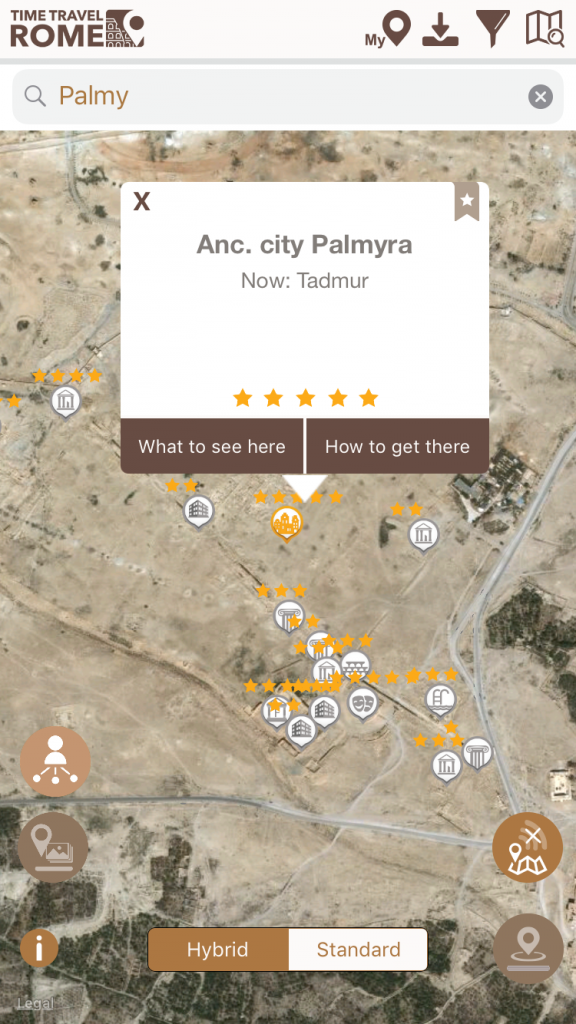

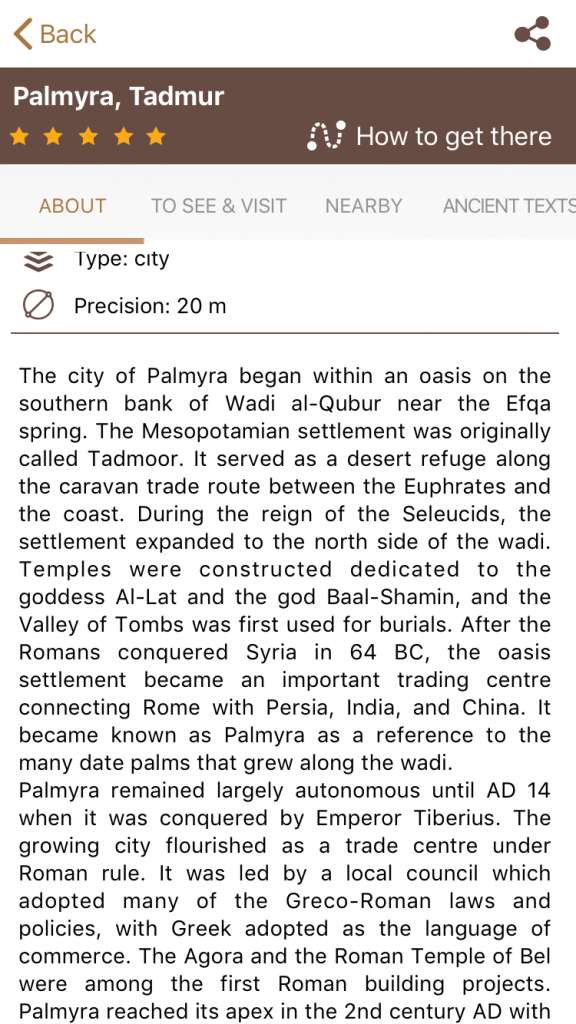

Though inhabited from the Neolithic Era, Palmyra reached its height of prosperity due to its location on the Silk Road and the heavy profits from the lucrative trade. With such affluence, the city was able to invest in large public buildings and monuments. Its success is evident in the wealth of archeological sites that survived to the modern day. Sadly, the site took serious damages as a result of militant occupation, but UNESCO is working to restore the site and reopen it to the public.

Even so, its ruins are extensive, and images from before the destruction reveal the former splendor that will hopefully soon be restored. In ancient times, Palmyra peaked in power in the middle of the third century A.D., as Zenobia of Palmyra expanded her influence and built an eastern empire to rival Rome itself. She maintained her rule for some years until her final showdown with Emperor Aurelian.

Palmyra Rising

Zenobia was born around 240 A.D., to a family of at least some status. She claimed her ancestry went back to Cleopatra and the Ptolemies, as well as Dido of Carthage. Her parents were Roman citizens, making her one too, and they educated her well. She was able to speak her native Palmyrene (a dialect of Aramaic) as well as Egyptian, Greek, and Latin. Al-Tabari, the Arabic source regarding her life, claims that her family put her in charge of their shepherds and flocks at a young age. She therefore became comfortable with a leadership role, even commanding the men in her father’s employ. She also learned to ride and developed lasting strength, endurance, and resilience. In her later ruling years, she apparently marched with her soldiers for long distances, and could hunt and drink with the best of them.

Around 258 A.D., she married Lucius Septimus Odaenthus, the Roman governor of Syria, and bore a son, Vaballathus. Odaenthus was himself a clever and ambitious man. In 260 A.D., Emperor Valerian attempted to retake Antioch from the Sassanid king, Shapur I. Instead he lost a devastating battle and found himself a prisoner in Persia. He lived the remainder of his life as a prisoner of Shapur, dragged around in chains and forced to be stool for the king when Shapur mounted his horse. Odaenthus secretly sought an alliance with Shapur. However, when the Sassanid king rejected him, he began a campaign against the Persians, claiming the noble cause of rescuing the captured and humiliated emperor. Though he did not recover Valerian, Odaenthus successfully drove the Sassanids out of Syria. Furthermore, a year later, Odaenthus put down Quietus, who had challenged Gallienius’s rule.

Zenobia Augusta

In gratitude for his actions, Valerian’s son Gallienius declared Odaenthus governor of the entire eastern region of the Roman Empire. Odaenthus held enough power and prestige to rule almost independent of Rome’s authority. However, in 266 A.D., he and his eldest, Herodes, son of his first wife, were assassinated. Vaballathus was too young to rule, and so Zenobia took charge as regent. She continued her husband’s schemes for expanding control and independence, though also being careful to never outright challenge Rome. In this way, she took Egypt, but claimed it was merely a campaign against one Timagenes, who had started a rebellion against Roman rule. Later authors believed Zenobia may have sent Timagenes into Egypt to raise rebels and provide her with the excuse she needed. She negotiated power in the Levant and Asia Minor, and began making trade agreements and political alliances without consulting Rome.

In chaos itself, Rome was either oblivious to the rise of Zenobia’s Palmyrene Empire and the threat it posed, or simply incapable of response. In her capital in Palmyra, Zenobia built a luxurious palace and surrounded herself with scholars and philosophers. Ancient historians describe her as a great beauty, as well as chaste, valiant, fiery, strong, and intelligent. Eventually she declared her son Augustus and herself Augusta, titles reserved for the royal family of Rome. Though not an outright declaration of rebellion, it was a significant move. The recently appointed Emperor Aurelian, a veteran of many wars and accomplished general, was not willing to overlook Zenobia’s growing power as his predecessors had been. As soon as he had calmed the situation in the northern Roman Empire, he and his armies marched toward Palmyra.

Aurelian Triumphs

The two forces met at the Battle of Immae. Aurelian successfully fooled the Palmyrenes with an old tactical trick. Pretending to retreat, his army drew Zenobia’s in before swinging around to surround the straggled line of tired soldiers. Zenobia and her top general escaped, though many of their men were slaughtered. Soon after, at a second battle near Emesa, they unfortunately fell for the same maneuver. Zenobia escaped the battle once again and retired to Palmyra, preparing for siege. When it became clear that she had no hope of victory, she attempted to flee to Persia by camel, but was captured. Aurelian’s men urged him to execute her, but he could not bring himself to order the death of a woman. Instead, he executed several of her top advisors, and brought her and her son back to Rome.

Sources disagree as to Zenobia’s final end. Zosimus claims she and her son leapt into the Bosphorus River and drowned. However, he later contradicts himself, saying she lived out her days in Rome. The Historia Augusta claims she was paraded through Rome in Aurelian’s triumph, bound in golden chains and covered in jewelry. However, many sources doubt that Aurelian would have wanted to place Zenobia in the triumph. The fact that a woman had gained so much power and been his opponent in battle may have been something he wished to downplay rather than emphasize. Several sources agree that Aurelian allowed her to live out her days in luxury, though he never allowed her to return home. He gave her a villa in Tibur, and she may have eventually married a Roman senator.

What to see in Palmyra now :

Up until 2015, Palmyra remained beautifully preserved. The main temples, colonnaded streets, theatre, agora, tombs, and other major buildings were all considered some of the best remaining Roman monuments. In 2015 and 2017, the militant group, ISIL, occupied the precinct. In separate acts of deliberate destruction, the group bombed or otherwise damaged much of the ancient city. Restoration has begun, and UNESCO is working alongside a number of archaeological associations and museums to continue repair work. A schedule is in place to re-open the site to tourists.

Palmyra on Timetravelrome app:

To find out more: Timetravelrome.

Author: written for Timetravelrome by Marian Vermeulen.

Sources: Sextus Aurelius Victor, Epitome De Caesaribus; Historia Augusta, The Two Valerians; Zonaras, Extracts of History; Al-Tabari, History of the Prophets and Kings; Zosimus, Historia Nova.

Header Photo: Temple of Bel complex in the background and the agora on left center in Palmyra, by Bernard Gagnon licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0