Like many settlements of the more remote Roman provinces, Carnuntum originated as a military outpost. Built sometime around the turn of the millennium, historical documents first mention the fort as the headquarters of Tiberius in his northern campaigns. A civilian city later developed alongside the fort. It quickly became a major trade hub with the Baltic regions and eventually the capital of the province of Pannonia. Today, several structures remain evident from Carnuntum’s ancient prominence. Additionally, reconstructions present an image of life in the past, and the city’s museum houses a number of exciting archaeological treasures. As headquarters for the Roman Army during the first century A.D., Carnuntum launched campaigns against a leader of the Germanic tribes named Maroboduus.

King of Bohemia

Born around 30 B.C., Maroboduus was the son of a noble of the Macromanni tribe. According to ancient Roman historians, he lived for a time in Rome during his youth. He was likely a hostage following the defeat of the Macromanni by Drusus. Because he became a favorite of the Emperor Augustus, he received impressive care and education. When he returned to Germania about 9 B.C., he had knowledge of Roman military strategy and imperial dreams. As a result, he quickly consolidated the German tribes under his leadership, and led them into the region known as Bohemia to avoid the fast-expanding Rome.

Though Maroboduus had no intention of entering war with Rome, he was ready to defend his Germanic Empire. Augustus soon considered him a threat, and sent Tiberius with twelve legions to Carnuntum with orders to attack Maroboduus. However, the war never happened. Shortly after the legions left Rome, a violent revolt broke out in northern Macedonia. All soldiers were dispatched there immediately, and the Senate insisted that Tiberius lead the action, so Tiberius reluctantly concluded a quick treaty with Marodobuus, recognizing him as King of Bohemia, and went with his legions to put down the unrest in Illyria.

You wish to support this blog? Download our app:

Prisoner of Rome

Marodobuus remained on shaky good terms with Rome during his rule. His ongoing conflict with Arminius, leader of the Cherusci tribe, pleased the Romans. Arminius was the general who defeated the Romans in the bloody Battle of Teutoburg Forest. After his victory, he sent the head of Publius Quinctilius Varus, the Roman commander, to Marobobuus in triumph. However, Maroboduus respectfully returned the head to Emperor Augustus. Despite this, he still remained neutral when Tiberius and Germanicus devastated the Cherusci in revenge for Teutoburg.

Maroboduus was eventually deposed by another young Macromanni noble in 19 A.D., and fled to Rome for sanctuary. Tiberius granted him safety, but remained wary of the German leader’s skill and abilities. In a speech to the Senate, he asserted that, due to “the greatness of the man, the violence of the peoples beneath his rule, [and] the nearness of the enemy to Italy …not Philip himself had been so grave a menace to Athens — not Pyrrhus nor Antiochus to the Roman people.” Tiberius never allowed Maroboduus to return to Germania. He detained him in Ravenna for eighteen years, until Maroboduus’s death in 37. A.D.

The Allure of Amber

Carnuntum quickly grew from a military headquarters into a thriving Roman city. One of the reasons for its rapid economic growth was its position on the ancient Amber Road, a trading route carrying the expensive, luxury item from the Baltic down to Italy. Baltic amber is the fossilized resin of a now extinct pine tree of prehistoric times. During the Bronze Age, it washed up frequently on the shores of the Baltic Sea, and local tribesmen used it as decorations, health charms, and religious symbols. Yet when the Baltic tribes first made contact with travelers from the Mediterranean world, they learned just how much foreigners were willing to pay for the seductive red-gold pieces. Trade flourished, and Baltic amber pieces traveled far afield. Pieces of amber in Etruscan ruins demonstrate its continued popularity in Italy, and with the rise of Rome, demand for amber skyrocketed.

It became a favorite status symbol among the elite, and was one of the five most important commodities of Rome. Pliny the Elder commented at one point that amber was so expensive that a small figure of a man carved from amber cost more than a living man at a slave market. Carnuntum grew to prominence at the hub of this trade, and archaeologists have uncovered many amber pieces there. Carnuntum became a municipium under Hadrian, housed Marcus Aurelius’s headquarters during his wars in Germania, and was the seat of Septimius Severus, governor of Pannonia, when, in 193 A.D., his soldiers proclaimed him Emperor. The city reached the height of its prosperity under the Severan Dynasty, and Caracalla named it a colonia. Carnuntum was eventually abandoned due to increasing barbarian invasions.

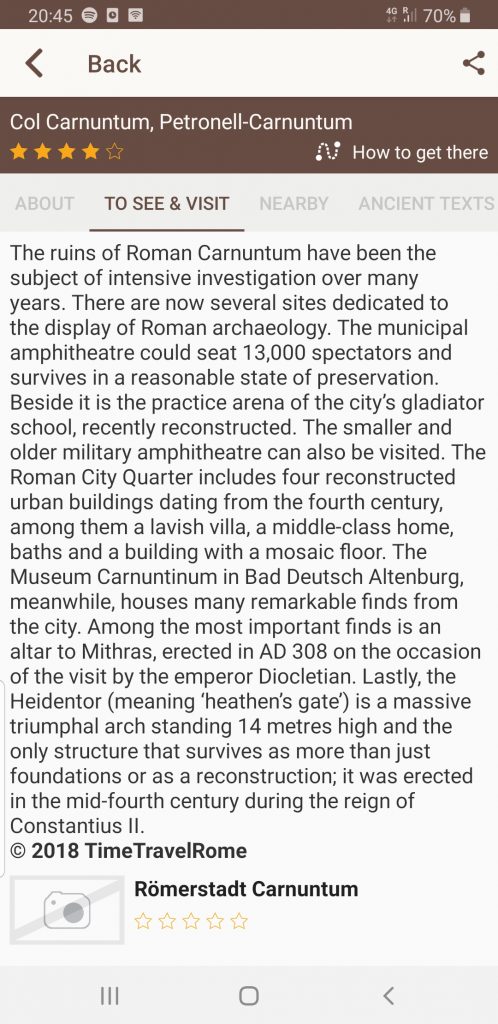

What to see here now :

The ruins of Roman Carnuntum have been the subject of intensive investigation over many years. As a result, there are now several sites dedicated to the display of Roman archaeology. The municipal amphitheatre could seat 13,000 spectators and survives in a reasonable state of preservation. Beside it is the practice arena of the city’s gladiator school, recently reconstructed. The smaller and older military amphitheatre is also available for visits. In addition, the Roman City Quarter includes four reconstructed urban buildings dating from the fourth century, among them a lavish villa, a middle-class home, baths and a building with a mosaic floor.

The Museum Carnuntinum in Bad Deutsch Altenburg, meanwhile, houses many remarkable finds from the city. Among the most important finds is an altar to Mithras, erected in AD 308 on the occasion of the visit by the emperor Diocletian. Lastly, the Heidentor (meaning ‘heathen’s gate’) is a massive triumphal arch standing 14 metres high and the only structure that survives as more than just foundations or as a reconstruction; it was erected in the mid-fourth century during the reign of Constantius II.

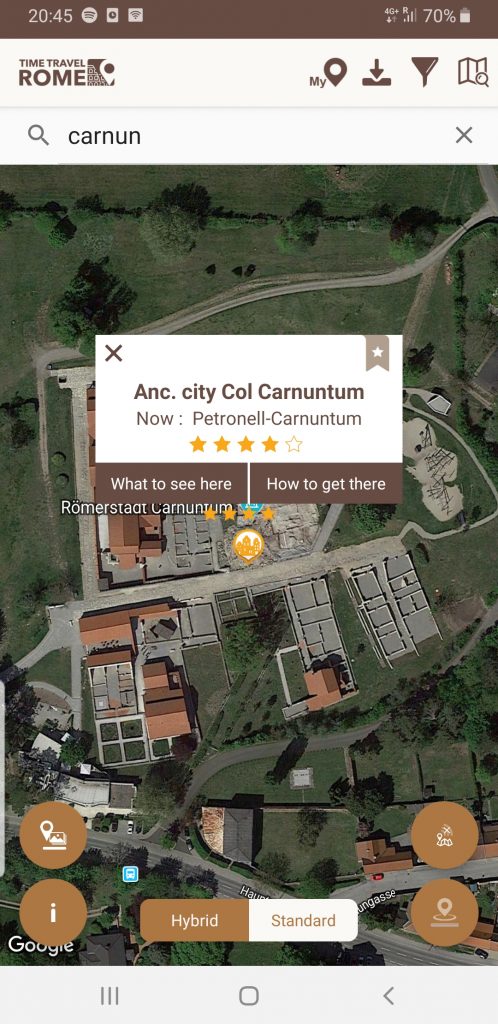

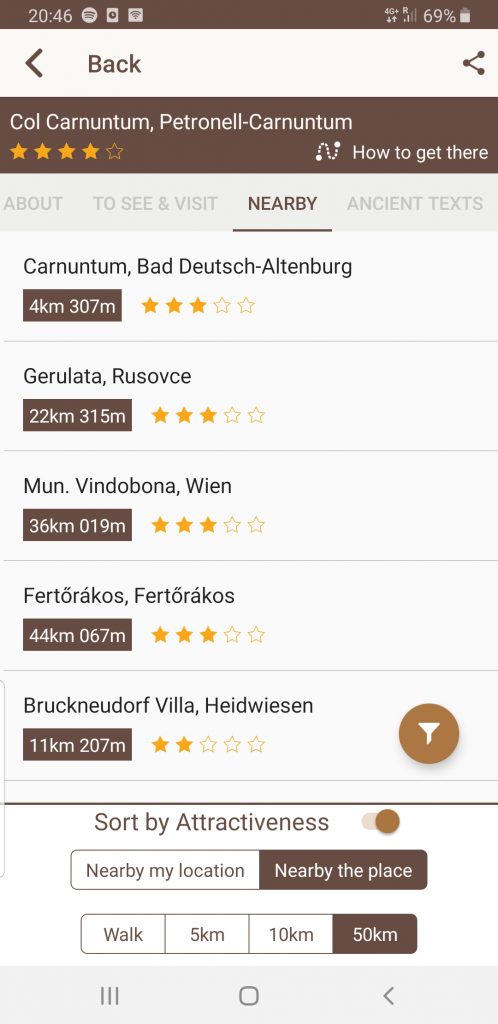

Carnuntinum on Timetravelrome app:

To find out more: Timetravelrome.

Author: written for Timetravelrome by Marian Vermeulen.

Sources: Tacitus, Annals; Cassius Dio, Roman History; Strabo, Geography; Velleius Paterculus, The Roman History.

Header Photo: Petronell – Heidentor by Bwag licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0