“Such was the end of Agrippa, who had in every way clearly shown himself the noblest of the men of his day.”

– Cassius Dio

Although ancient writers accepted the rumors that Augustus sent Agrippa away due to rising jealously between Agrippa and Marcellus, the nephew of Augustus, the long standing loyalty and esteem between the two men, from their earliest years together to the point of sharing a resting place, hardly seems to support that conclusion. In fact, it is far more reasonable to accept the modern speculation that Agrippa instead left Rome on an important, secret diplomatic mission. That the trust and affection between Augustus and Agrippa continued unchecked, even during Agrippa’s absence of Rome, can easily be seen in their actions, even as rumors claim otherwise.

Honoring Friends

Agrippa’s public projects in Rome were a great boon to the city, and constructed at his personal expense. Cassius Dio mentions that a number of important figures commissioned buildings in Rome, but often it was done ostentatiously, an attempt to bolster their own fame and glory with little thought to the structure’s overall use. In contrast, Agrippa consulted personally with Augustus to choose the projects that would most benefit Rome and its people. When completed, he did not “claim in the slightest degree a share in the glory of them, but used the honours which the emperor bestowed, not for personal gain or enjoyment, but for the benefit of the donor and of the public.”

In his design for the Pantheon, Agrippa greatly desired to name the structure after his good friend, and to place a statue of Augustus among those of the gods. Augustus diplomatically declined, and Agrippa finally agreed. Instead, he put a statue of Julius Caesar in the main chamber, and flanked the ante-room with a statue of Augustus and of himself. Cassius Dio again insists that “this was done, not out of any rivalry or ambition on Agrippa’s part to make himself equal to Augustus, but from his hearty loyalty to him and his constant zeal for the public good; hence Augustus, so far from censuring him for it, honoured him the more.” When Agrippa’s house on the Palatine Mount burned down, Augustus insisted that Agrippa move in with him and share his own extravagant home.

Powers of the Princeps

Where many rulers would fear to give a potential rival too much autonomy, particularly one as beloved by the people as Agrippa, Augustus lavishly bestowed authority to Agrippa, raising him to be the second most powerful man in Rome, and entrusted him with the highest of ceremonies. When Augustus fell ill just before the important marriage of his daughter Julia to his nephew, Marcellus, he asked Agrippa to hold the festival in his place. He pressed for a law which stated that whenever Agrippa was sent on business of the Republic, no-one held power greater than his. In fact, Augustus eventually gave so much authority to Agrippa that Agrippa was effectively at the same level as the princeps. The only difference in their powers being that Augustus was granted tribunicia potestas for life, while that power was renewed every five years for Agrippa.

Agrippa had long been Augustus’s presumed heir. When the princeps had fallen desperately ill and was not expected to survive, he sorted his affairs in preparation for his death, and handed his ring to Agrippa. After the death of Marcellus, Augustus requested that Agrippa divorce his own wife and marry Julia, thus tying Agrippa even closer as his son-in-law. Agrippa agreed. However, having an heir that is the same age as his predecessor presents obvious disadvantages. As a result, when Julia gave birth to two sons, Gaius and Lucius, Augustus immediately adopted them and appointed them as his official heirs.

Missed Farewell

Agrippa remained Augustus’s steadfast general during this period, taking on campaigns in Sicily, Gaul, Spain, Syria, and Pannonia. He even settled unrest and riots in Rome while Augustus was away. In all these successes, he remained, according to all sources, humble and modest. He refused triumphs from Augustus on multiple occasions, and did not engage in the practice of sending boastful reports of his exploits back to Rome. It was on his return from the Pannonia campaign in 12 B.C. that disaster fell. Upon reaching the region of Campania, quite possibly in the villa at Boscoreale that later passed to his son, Agrippa Postumus, Agrippa became seriously ill. Messengers hurried to Athens, where Augustus was overseeing the prestigious Panathenaic Festival. Augustus immediately abandoned his duties overseeing the games and rushed to Campania, but he was too late to bid his friend farewell.

Devastated, Augustus brought Agrippa’s body back to Rome and insisted that he lie in state in the Forum. On the day of the funeral, he delivered the funeral oration himself, and arranged a procession that was very similar to his plans for his own funeral. Even though Agrippa owned a burial site in the Campus Martius, Augustus laid Agrippa’s body to rest in his own family mausoleum. He felt the loss for a long time, spending over a month in mourning and continuing to issue honors and memorials for his friend. Several coins depicting Agrippa were struck at this time, and Augustus named Julia’s third son after his deceased father. He personally oversaw the education and upbringing of all of Agrippa’s children as if they were his own, though tragically he outlived both Gaius and Lucius.

Agrippa’s Legacy

Agrippa is remembered fondly by all of the ancient historians who wrote of him. He is lauded as a loyal subordinate to Augustus as well as being hugely beloved of the Roman people. In his will, he left his public buildings, baths, and gardens to the people of Rome, along with a generous endowment to ensure that his baths would remain free for use. He left most of his estates to Augustus, most of which the emperor turned over to the state, as well as giving out a gift, as requested by Agrippa, of four hundred sesterces* to each citizen.

Agrippa was a writer and a geographer. Among his works he left behind an autobiography, which sadly has yet to be found, and also a comprehensive chart of the Roman Empire, which Augustus had engraved in marble and placed on a colonnade. Agrippa is the one who established the official distance of a Roman foot, using his own foot size as the standard, and his name adorns the Via Agrippa, a network of roads throughout Gaul whose construction he commissioned.

He is remembered as having “used the friendship of Augustus with a view to the greatest advantage both of the emperor himself and of the commonwealth. For the more he surpassed others in excellence, the more inferior he kept himself of his own free will to the emperor; and while he devoted all the wisdom and valour he himself possessed to the highest interests of Augustus, he lavished all the honour and influence he received from him upon benefactions to others.”

*Though calculating the value of the sesterce is a difficult proposition, and various valuations place it anywhere from 50 cents to 50 dollars, calculations based on relative labor rates suggest that one interpretation of the amount given in Agrippa’s will would equal about 200 US Dollars or 180 Euros.

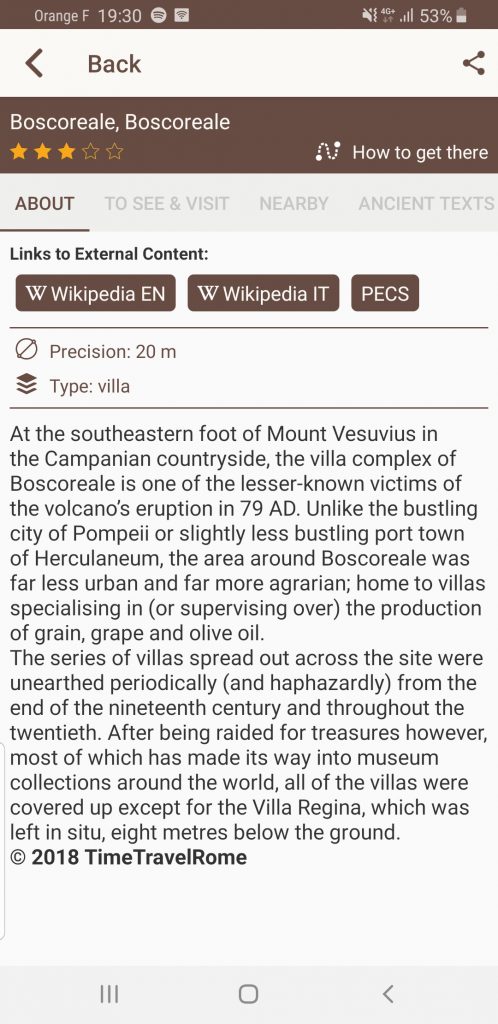

What to See in Boscoreale now ?

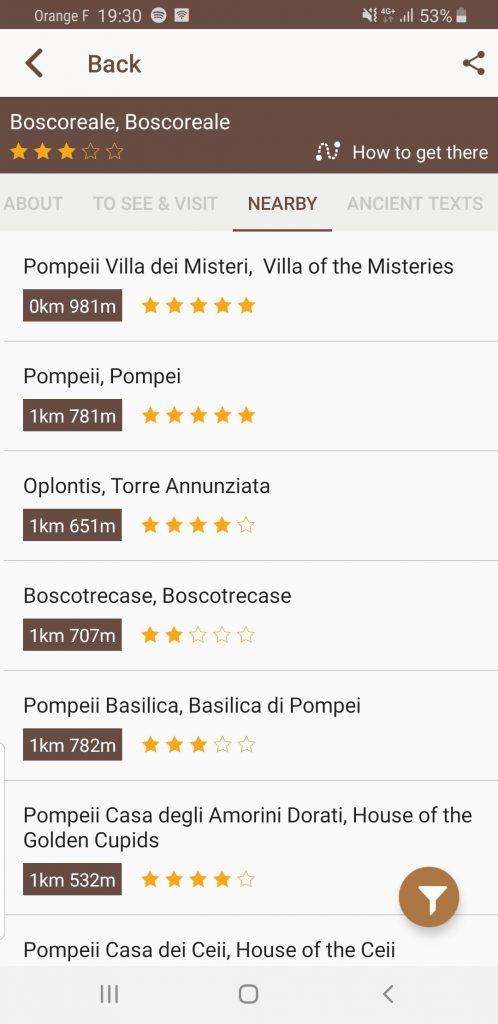

The only villa you can visit today is the Villa Regina, completely restored in 1991. Though dating to the first century BC, the villa was expanded twice the following century, first during the Augustan Age then during the Julio-Claudian period. Unlike the other villas found in the area, Villa Regina was less a luxurious country retreat and more a well-furnished, comfortable working farm: as evidenced by the remains of a wine press, a subterranean wine cellar and vast amounts of pottery. Finds from the other villas, including the ornate Villa of Agrippa Postumus, are spread out across the Metropolitan Museum of New York, Art Institute of Chicago, Museum of Naples and the Louvre, just to name a few. Or, more locally, the Antiquarium of Boscoreale is home to some interesting artefacts and reproductions.

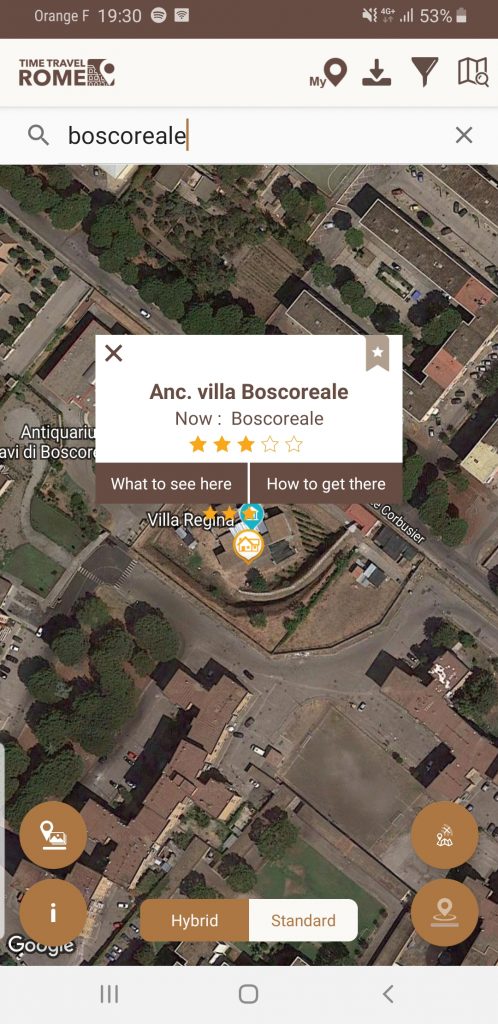

Boscoreale on Timetravelrome App:

Sources: Cassius Dio, Roman History; Suetonius, Life of Augustus; Tacitus, Annals

Author: Written for Timetravelrome by Marian Vermeulen

Header image: Villa Regina, Boscoreale. Photo b Norbert Nagel . Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0