Thus did Pertinax, who undertook to restore everything in a moment, come to his end.”

– Cassius Dio

Christened Publius Helvius Pertinax, the future emperor enjoyed a humble and practical beginning, which informed his decisions throughout his life. He even maintained his business enterprises in Vada Sabatia, just south of Savo, after being named emperor. Though a favorite of the people and the Senate due to his unassuming respect of the Senators and his careful administration of the empire, he tried to make improvements too suddenly and incurred the wrath of the Roman Praetorians, to his demise.

Childhood and Army Life

Pertinax’s father was no noble, rather he was a freedman named Helvius Successus. The cognomen Pertinax is similar to “persistence,” something the Historia Augusta claims was given to the young boy by his father in honor of his own diligence in timber trade. There is some discrepancy between the sources as to Pertinax’s hometown, but Cassius Dio’s claim that he was born in Alba Pompeia, a city in Luguria just barely to the south of Savo, modern day Savona, is generally accepted. He is frequently mentioned as “going home” to his father’s workshop in a nearby town, and Cassius Dio served in the Senate at the same time as Pertinax, even attending his funeral eulogy. There is little reason to doubt his information.

Pertinax’s father wished for his son to receive some education, and so he sent him to learn literature and arithmetic. He particularly excelled in grammar under the tutelage of Sulpicius Apollinaris, and pursued a career as a grammar instructor himself. Quickly realizing that there was little money to be made as a grammar tutor, he instead joined the Roman Army, and quickly earned recognition and promotions for his actions in the Parthian War. He served in many different regions of the Empire, as a soldier in Britain, squadron commander in Moesia, supply officer in northern Italy, and commander of the German naval fleet, finally ending up in Dacia.

Earning Imperial Attention

Pertinax lost the Dacia command due to the schemes of some rivals, who convinced the emperor, Marcus Aurelius, that Pertinax was not to be trusted. However, Pertinax had developed a relationship with Claudius Pompeianus, the emperor’s son-in-law, and the latter took him as his aid in order to begin rebuilding his reputation, and then later pushed through Pertinax’s enrollment in the Senate. Eventually, the plot against him was discovered. To make it right, Marcus Aurelius gave him the rank of praetor and the command of the First Legion. After distinguishing himself once again, Marcus recommended him for a consulship, and praised his skill and quality of character frequently. Over the following years, Pertinax continued to serve loyally throughout the empire as governor of first Moesia, then Dacia, and later Syria.

It was about this time, shortly after the death of Marcus Aurelius that the Historia Augusta claims Pertinax began to grow ambitious and money hungry. His ambitions were halted, however, when Commodus’s Prefect of the Praetorians, Tigidius Perennis, ordered him to leave Rome, essentially softly exiling him to the country. Pertinax when home to Liguria and took charge of his father’s old ’loth-making shop, as well as buying up and managing numerous local farms and business to add to his holdings. After Perennis became embroiled in a plot to overthrow Commodus, the emperor ordered his execution and invited Pertinax back into favor, asking him to take over command of Britain. Upon returning from this post, Commodus appointed him consul for the second time.

Acclaimed Emperor

Pertinax was still serving as consul when Commodus’s mistress, chamberlain, and prefect of his bodyguard conspired to assassinate their emperor. Pertinax was apparently unaware of the plot, but the three came to him after Commodus was dead and asked him to succeed as emperor. Upon winning the support of the army, though begrudgingly, Pertinax went before the Senate, told them the army had acclaimed him Emperor, but insisted that he did not want the office and would immediately resign it. However, the Senate quickly begged him to take the office, and affirmed him as emperor while declaring Commodus a public enemy.

Pertinax received a warm welcome, for Commodus had been universally hated, particularly by the Senators who feared his violent, changing moods and frequent executions. Furthermore, Pertinax was deeply enamored of traditional Rome, and respectful of the Senate. Dio Cassius, a contemporary Senator, praised him highly in his history, saying that “he showed not only humaneness and integrity in the imperial administrations, but also the most economical management and the most careful consideration for the public welfare.” He also pardoned many of those whom Commodus had killed unjustly and saw to their exhumations and proper burials. Many Romans immediately burst into tears for their family and friends, having been too frightened of Commodus even to mourn.

The Modest Princeps

Despite his newly found power, Pertinax remained circumspect and humble. He would not accept the title of Augusta for his wife or Caesar for his son. In fact, he refused to allow them to be raised in the palace. On his first day as emperor he divided all the wealth he had between the two of them and sent them to live with their grandfather in the country. He visited them there as often as he could, “but rather as their father than as emperor” (Cassius Dio, 8).

He was a somewhat portly older man with a long beard, though he maintained a regal bearing. Although he was not an immensely intelligent emperor, he enjoyed having literary discussions with his wife and a former teaching friend over dinner, and possessed enough skill in speaking to be described as suave. Though generally a kind and friendly emperor, Pertinax maintained a stingy nature, never throwing extravagant parties, serving less than luxurious fare in half portions, and having none of the over-generous qualities of some of his predecessors.

A Reign Cut Short

It was this quality that eventually caused Pertinax’s downfall, for the Praetorians began to feel that he had not given them their due, and he also forbade them from looting and despoiling defeated enemies. He made enemies within the palace as well with the freedmen and courtiers who had enjoyed lavish lifestyles under Commodus that Pertinax would not permit. Though the palace members had no means to stage an uprising, the Praetorians began to plot against him, headed by Laetus, the old prefect of the imperial guards who had first placed Pertinax on the throne.

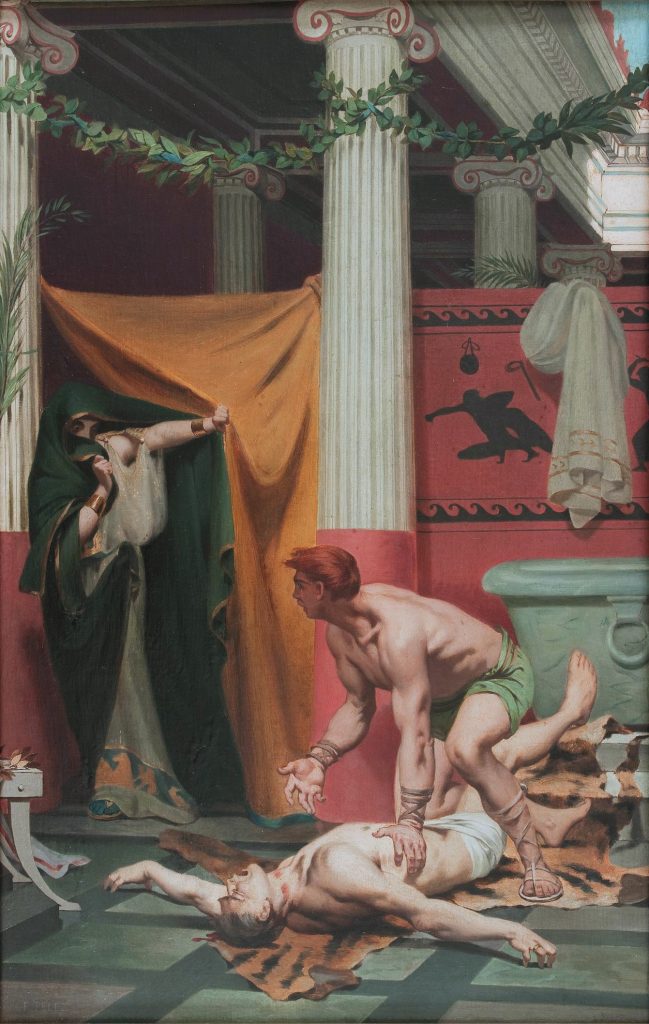

They attempted a coup with the current consul, Falco, as the intended successor, but Pertinax discovered the plot. Even so, he would not allow the Senate to sentence Falco to death, but instead exiled him to the country. Laetus, however, took the failed rebellion as an opportunity. Executing many Praetorian soldiers who had been involved, he insisted that it was on the emperor’s orders, and thus worked them into a fury. A large group marched on the palace, and the disgruntled courtiers opened the gates and doors for them.

Rather than concealing himself or sending his personal guard to overwhelm them, Pertinax thought he could talk them down and went out to meet them. He was almost correct. Upon seeing him they were ashamed, lowering their eyes and sheathing their weapons. All except one soldier, who “leaped forward exclaiming, “The soldiers have sent you this sword,” and forthwith fell upon him and wounded him.” The other soldiers recovered their resolve and joined in, killing Pertinax and Eclectus, the chamberlain who had initially conspired against Commodus and now remained steadfastly loyal. He died attempting to defend his emperor.

Aftermath

Pertinax had reigned for only eighty-seven days. The soldiers, caught up in the excitement of their rebellious murder, mounted his head on a spike and carried it through the streets. However, Pertinax’s successor, Didius Julianus, did recover the body and give the former emperor a proper burial, and after the death of Julianus, the Senate declared Pertinax a god. Pertinax’s rule was an interestingly divided one. As much as the soldiers and his palace staff grew to hate him, the Senate and the people adored him, and were infuriated by his death.

His historical legacy remains a largely positive one, influenced by the eyewitness account of Cassius Dio who obviously held him in high regard. According to Cassius, Pertinax’s only true failing was his attempt to fix the problems of the empire too quickly. “He failed to comprehend, though a man of wide practical experience, that one cannot with safety reform everything at once, and that the restoration of a state, in particular, requires both time and wisdom.”

What to See in Savona now ?

While nothing remains of Roman Savo itself, a Roman villa can be found northeast of modern Savona in its own archeological park. The site is mainly limited to wall foundations, but it gives an idea of how large these farming hubs could be (The park now appears to be permanently closed to visitors. However, the villa walls and foundations can still be seen from outside the site). In Savona’s historical center, the local archeological museum in the medieval castle contains a good collection of pottery and tools used by the Celts who inhabited the area.

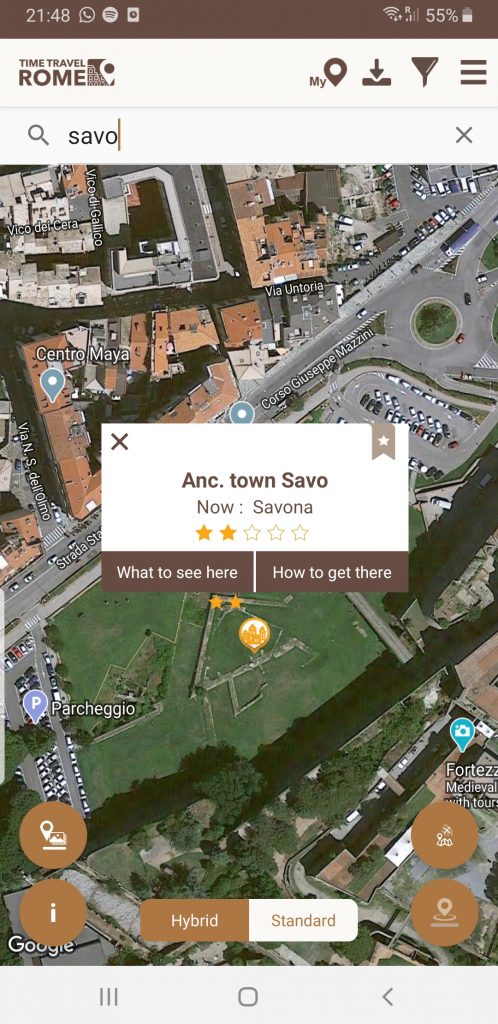

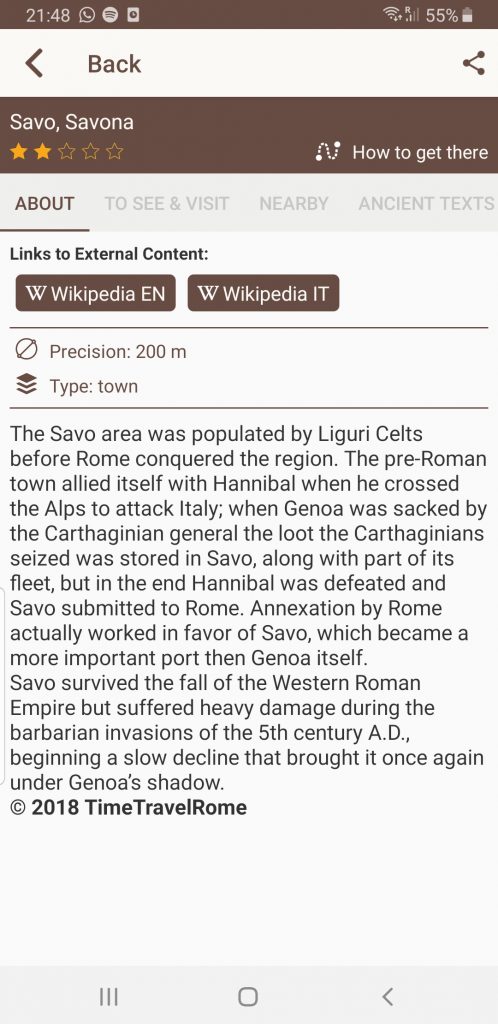

Savo on Timetravelrome App:

Author: Marian Vermeulen for Timetravelrome

Sources: Historia Augusta, Pertinax; Cassius Dio, Roman History

Header image: Pertinax Aureus minted btw 1st January – 28th March 193. Obverse: Laureate head of Pertinax right. Reverse: Aequitas standing l., holding scales and cornucopiae. Source: Numismatica Ars Classica NAC AG Auction 117 Lot 313. Picture is used by permission of NAC.